13. Your Family Map

When I first started working with entire families, I was struck by the tremendous unrelated activity that went on in all directions: physically through bodily movement and psychologically through double messages, unfinished sentences, and so on. More than anything else I was reminded of the can of angleworms my father used to take as bait on fishing trips. The worms were all entangled, constantly writhing and moving. I couldn’t tell where one ended and the other began. They really couldn’t go anywhere except up, and down, around, and sideways, but they certainly gave the impression of aliveness and purpose. Had I been able to talk to one of those worms to see how he felt, it is my feel- ing that he would have told me the same kinds of things I have heard from family members over the years: Where am I going? What am I doing? Who am I?

The comparison between the way many families conduct themselves and the purposeless, tangled writhing of these worms seemed so apt that I termed the network that exists among family members a can of worms.

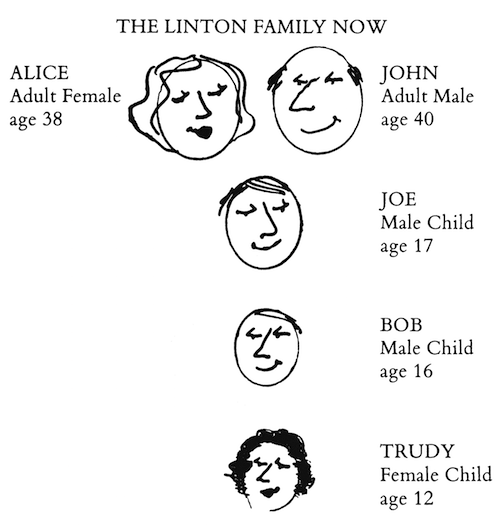

To show you what your family network is and how to map it will be the goal of this chapter. I think the best way to go about it is to take an imaginary family, the Lintons, and show you how their network works for and against them. No one can ever actually see this network, incidentally, but you can certainly feel it, as the exercises outlined in this and the following chapter will amply demonstrate to you.

All right. Here are the Lintons as individuals and as their family is today.

Tack a large sheet of paper to the wall where all of you can see it clearly. Begin the map of your family by drawing circles for each person, using a felt-tipped pen. Your family may now include a grandparent or other person as part of your household. If so, add a circle for that person on the row with the other adults.

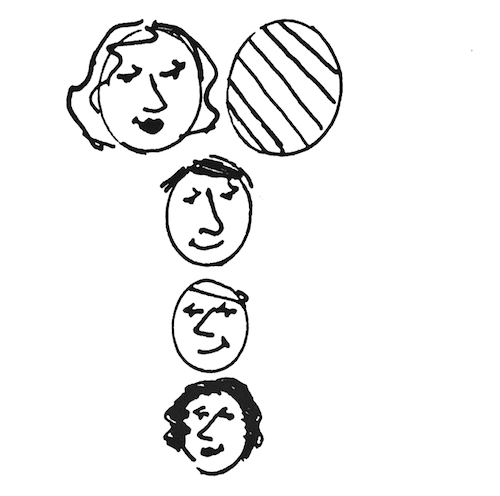

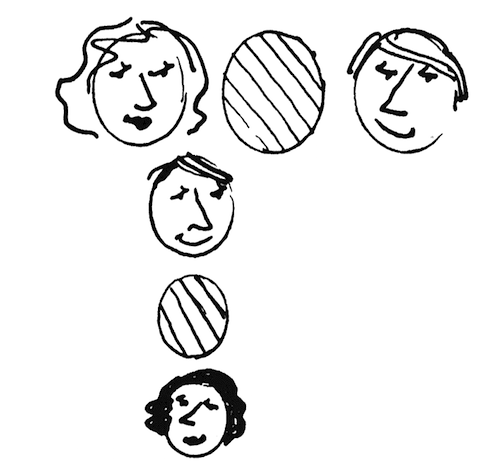

If someone was once a part of your family but is gone now, represent her or him with a filled-in circle. If the husband or father is dead, has deserted the family or divorced his wife, and his wife has not remarried, your map would show it as follows:

If the woman has remarried, it would be shown thus:

If the second child died or was institutionalized, your map would look this way:

I believe that anyone who has ever been part of a family leaves a definite impact. A departed person is often very much alive in the memories of those left behind. Frequently, too, these memories play an important role——often a negative one——in what is going on in the present. This doesn’t have to happen. If the departure has not been accepted, for whatever reason, the ghost is still very much around and often can disrupt the current scene. If, on the other hand, the departure has been accepted, then the present is clear as far as the departed one is concerned.

Each person is a separate self who can be described by name, physical characteristics, interests, tastes, talents, habits——all the qualities that relate to him or her as an individual.

So far our map shows the family members as islands, but anyone who has lived in a family knows that no one can remain an island for long. The various family members are connected by a whole network of ties. These links may be invisible, but they are there, as solid and firm as if they were woven of steel.

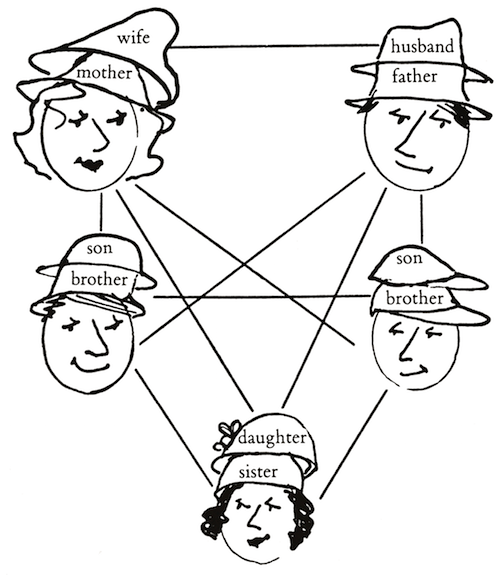

Let's add another strand to our network: pairs. Pairs have specific role names in a family. The illustration below shows the pairs in the Linton family with their role names.

Roles and pairs in the family fall into three major categories: marital, having the labels of husband and wife; parental-filial, having the labels of father-daughter, mother-daughter, father-son and mother-son; and sibling, having the labels of brother-brother, sister-sister, and brother-sister. Family roles always mean pairs. You can't take the role of a wife without a husband, nor father or mother without a son or daughter, and so on.

Beliefs about what different roles mean can differ. Each role evokes different expectations. It’s important to find out what the various roles mean to each family member.

When families come to me a little mixed up, one of the first things I do is ask for each member’s ideas about what his or her role means. I remember one couple very vividly. She said, “I think being a wife means always having the meals on time, seeing that my husband’s clothes are in order, and keeping the unpleasant things about the children and the day from him. I think the husband should provide a good living. He should not give the wife any trouble.”

He said, “I think a husband means being the head of the house, providing income, and sharing his problems with his wife. I think a wife ought to tell her husband what’s going on. She ought to be a pussycat in bed.”

You can see that both were practicing what they thought the roles were; they didn’t know how far apart they actually were in these important areas. Never having spoken about it, they had just assumed their views on their respective roles were the same. When they shared their ideas, some new understanding developed between them, and they achieved a much more satisfying relationship. I have seen this particular couple’s experience over and over again in troubled families that come to me for help.

What about your family and your respective role expectations and definitions? Why not all sit down and share what you think your role is, and those of your spouse and your offspring as well? I think you’ll be in for some surprises.

Now let’s examine another facet of this role business. Alice Linton is a person who lives and breathes and wears a certain dress size. She is also a wife when she is with John, and a mother when she is with Joe, Bob, or Trudy. It might be helpful if we think of her roles as different hats she puts

on when the occasion demands. Aside from her self-role, which she wears all the time, Alice uses a particular hat only when she is with the person who corresponds to the role- hat. So she is constantly putting on and taking off hats as she goes through her day. If she or john were to wear all their role-hats at once, they would look like this, and it could get a little top-heavy.

Now add the network lines to your family map, linking every member with every other member. As you draw each line, think for a moment about that particular relationship. Imagine how each of those two people involved feels about that connection. All of the family should share in this exercise, so each can try to feel what the different relationships are like

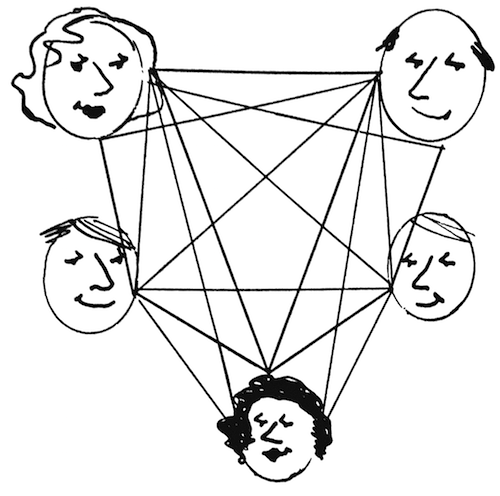

So far I have presented the Lintons to you as selves and pairs——five selves and ten pairs. If this were all there were to the map, living in a family would be quite an easy matter. When Joe arrived, however, a triangle came into being. Here the plot begins to thicken, for the triangle is the trap in which most families get caught. I’ll talk more about triangles later, but first let's add the network of triangles to the Linton family map.

Now the Lintons’ network looks like this. It’s pretty hard to see any one part of it clearly, isn’t it? You can see how the triangles obscure and complicate things. In families we don’t live in pairs; we live in triangles.

When Joe was born, not one, but three triangles were formed. A triangle is always a pair plus one and, since only two people can relate at one time, someone in the triangle is always the odd one out. The whole nature of the triangle changes depending on who is odd one out, so what looks like one triangle actually is three (at different times).

The three triangles above consist of john, Alice, and joe. In the first, john is the odd one, watching the relationship of his wife and son. In the second, Alice watches her husband and son together. In the third, little Joe watches his father and mother together. How troublesome any particular triangle is may depend on who is the odd one out at the moment and whether he or she feels bad about being left out.

There is truth to the old saying, “Two’s company, three’s a crowd.” The odd person in a triangle always has a choice between breaking up the relationship between the other two, withdrawing from it, or supporting it by being an interested observer. The odd person’s choice is crucial to the functioning of the whole family network.

All kinds of games go on among people in triangles. When a pair is talking, the third may interrupt or try to draw their attention. If the pair disagrees about something, one may invite the third to become an ally; this changes the triangle by making one of the original pair the odd one out.

Can you remember a time recently when you were with two other people? How did you handle that triangle? How did you feel? How are triangles handled in your family?

Families are full of triangles. The Linton family of five has thirty triangles:

John/ his wife/ his first son

John/ his wife/ his second son

John/ his wife/ his daughter

]ohn/ his first son/ his second son

John/ his first son/ his daughter

John/ his second son/ his daughter

Alice/ her husband/ her first son

and so on.

Triangles are extremely important because the family’s operation depends in large part on how triangles are handled.

The first step toward making a triangle bearable is to understand very clearly that no one can give equal attention to two people at the same time. Maybe the best idea is to approach the inevitable triangle as people do with Texas weather: stick around awhile, and it will change.

The second step, when you are the odd person, is to put your dilemma into words so that everyone can hear. The third step is to show by your own actions that being the odd one out isn’t a cause for anger or hurt or shame. Problems arise when people feel that being on the outside means they are no good. Low self-worth!

To live comfortably in a triangle, it seems to me that one needs certain feelings about oneself. An individual has to feel good about him- or herself and be able to stand on two feet without leaning on someone else. He or she can be the odd one temporarily without feeling bad or rejected. She or he needs to be able to wait without feeling abused, talk straight and clearly, let the others know what she or he is feeling and thinking, and not brood or store up bad feelings.

If you glance again at the Lintons’ family map and triangles, you can appreciate how complex family networks are. The concept of the can of worms may be more understandable to you, too.

Draw your family’s can of worms by adding all the triangles to your family map. Using a different colored pencil or ink may help distinguish the triangles from the pairs. Again, as you draw, think of the relationship that each line represents. Among any three people you will be drawing only one triangle, although three actually exist. Think of how that triangle looks from each person’s point of view.

The Lintons’ network did not develop overnight. It took six years to gather the people now represented in the network——possibly eight years, if you consider the two years john and Alice courted. Some families take fifteen or twenty years to assemble their casts. Others take one or two years, and some never finish because the core (the couple in charge) keeps changing.

Whenever the Lintons are all together, forty-five different units are operating: five individuals, ten pairs, and thirty triangles. Similar elements exist in your family. Each person has his or her own mental picture of what each of these units is like. john may look very different to his wife Alice than to his son Bob. Alice may see her relationship to Bob one way; Bob would see it differently. John's picture is probably quite different from either of theirs. All these varying pictures are supposed to fit together in the family, whether or not the individuals are aware of them. In nurturing families, all of these elements and everyone’s interpretation of them are out in the open and can easily be talked about. On the other hand, troubled families are either not aware of their family pictures or are unwilling or unable to talk about them.

Many families have told me they feel frustrated, physically tight, and uncomfortable when the whole family is assembled. Everyone feels constant movement, being pulled in many directions. If family members could be made aware of the can of worms in which they are trying to function, they wouldn’t be so puzzled and uncomfortable.

When families see their network for the first time and fully realize how tremendously complicated family living really is, they often tell me they feel great relief. They realize they don’t need to be on top of everything all the time. Who can keep track or control of forty-five units at once? Individual members can have a much easier time together because they didn’t feel the necessity to control things; they became more interested in observing what is happening and in planning creative ways to make the family function better.

The challenge in family living is to find ways each individual can participate or be an observer of others without feeling he or she doesn’t count. Meeting this challenge involves not being a victim of our old villain: low self-esteem.

A family’s can of worms exerts tremendous push-pull pressures on the individual. It puts great demand on each one. In some families it is difficult to be an individual at all. The larger the family, the more units to be dealt with, the more difficult it is for each family member to get a share of the action. I certainly don’t mean to imply that big families are always failures. On the contrary, some of the most nurturing families I know have large numbers of children.

Even so, the more children that come into the family, the more pressure on the marital relationship. A family of three has only three self-pair triangles; a family of four has twelve; a family of five has thirty; and a family of ten has 280 triangles! Each time a new person is added, the family’s limited time and other resources have to be divided into smaller portions. A larger house and more money may be found, but the parents still have only two arms and two ears. And the airwaves can still carry only one set of words at a time without total bedlam.

What often happens is that the pressure of parenting gets so overwhelming that very little of the self of either parent finds expression, and the marital relationship grows weak with neglect. At this point many couples break up, give up, and run away. They have starved as individuals, failed as mates, and probably aren’t doing very well as parents, either. Frustrated, turned off, emotionally dying adults don’t make good family leaders.

Unless the marital relationship is protected and given a chance to flower and unless each partner has a chance to develop the family system becomes crooked and the children are bound to be lopsided in their growth.

Being good, balanced parents is not impossible. It is just that parents must be particularly skillful and aware to maintain their selfhood and keep their marriage partnership alive when the can of worms is so full. Such parents will be in charge of nurturing families. They are living examples of the kind of family functioning that channels pressures in the family network into creative, growth-producing directions.