15. The Family Blueprint

Two big questions present themselves to every parent in one form or another: “What kind of a human being do I want my child to become?" and “How can I go about making that happen?" From the answers to these questions, the family blueprint develops. Since there are two parents, each may come up with different ideas. How you, as parents, handle those differences is a model in itself for your child. If the relationship with your partner is good, you can deal with these differences without putting an unnecessary burden on the Child. Your answers to the above questions and your modeling are your design, your blueprint, for people-making. Every parent has some kind of answer to these questions. The answers may he clear, vague, or uncertain, but they are there.

Under the best of circumstances, the parenting job is anything but easy. Parents teach in the toughest school in the world: The School for Making People. You are the board of education, the principal, the classroom teacher, and the janitor, all rolled into two. You are expected to be experts on all subjects pertaining to life and living. The list keeps growing as your family grows. Further, there are few schools to train you for your job, and there is no general agreement on the curriculum. You have to make it up yourself. Your school has no holidays, vacations, unions, automatic promotions, or pay raises. You are on duty, or at least on call, 24 hours a day, 365 days a year, for at least 18 years for each child you have. Besides that, you have to contend with an administration that has two leaders or bosses, whichever the case may be.

Within this context you carry on your peoplemaking. I regard this as the hardest, most complicated, anxiety-ridden, sweat-and-blood-producing job in the world. Succeeding requires the ultimate in patience, common sense, commitment, humor, tact, love, wisdom, awareness, and knowledge. At the same time, it holds the possibility for the most rewarding,joyous experience of a lifetime, namely, that of being successful guides to a new and unique human being. What parent has not felt the juices flow when a child says, with eyes full of lights and twinkles, “Gee, Mom——Dad——you’re great.”

Peoplemaking includes a generous measure of trial-and -error experience. You learn most through your on-the-job training. Previous preparation helps, of course. Parenting courses and seminars that include role-playing and other experimental exercises are also quite helpful. The role-playing particularly helps give you a sense of options and choices.

I am reminded of the story of an unmarried psychologist who wrote his thesis on how to bring up children. He titled it “Twelve Requirements for How to Bring Up Children.” Then he married, had one child, and changed the title to “Twelve Suggestions for How To Bring Up Children.” After the next child, his title changed to “Twelve Hints on How to Bring Up Children.” In the wake of the third child, he stopped giving the lectures. All this is to say there are no hard-and-fast rules for bringing up children. There are only guides that need to be modified for each child and each parent.

I think most parents would describe the kind of person they want their child to become in pretty much the same way: honest, self-respecting, competent, ambitious, clean, strong, healthy, bright, kind, good-looking, loving, humorous, and able to get along well with others. “I want to be proud of my child,” a parent will say. Do these qualities fit into your picture of a desirable person? What would you add or delete?

The question is how parents can lead a teaching process that will achieve what they want. Here again, congruence on the part of parents is a most useful skill.

The combination of the “what” and the “how” is what I am focusing on in this and the next chapter. To go further, I will deal with the goals and values parents hope their children will have, and the ways they can achieve this. Blueprints vary from family to family. I believe some blueprints result in nurturing families, some result in troubled ones. It is important that you have a clear picture of what the differences might be.

Perhaps as you read this, you can let yourself be aware of what kind of blueprint you are using. Maybe you can look critically at how your plan is working for you and your family, now, at this point. I hope you will get some ideas about how you can change whatever isn’t working too well right now. You may also find support for what you are already doing and you may notice ways to extend and enrich your current practices.

Many families are started by adults who are in the position of having to teach their children what they have not yet learned themselves. For example, a parent who has not learned how to control her or his temper cannot very well teach a child how to do this. There is nothing like raising a child to show up adult learning gaps. When such a gap appears, wise parents become students along with the children and they learn together.

The best preparation for parenthood that I know is for the parents to develop an openness to new things, a sense of humor, an awareness of themselves, and a freedom to be honest. When adults enter into making a family before they have achieved their own maturity, the process is infinitely more complicated and hazardous——not impossible, just rough. It can also be great fun. Who is perfect anyway?

Fortunately, changes can be made at any point in any person’s life, if one is willing to risk doing it. Please remember to start your change from a perspective of knowing you are always doing the best you can. Through hindsight, we always see how we could have done better. That is the nature of learning. Knowing you’re doing your best will help you create the confidence to go beyond where you are now.

You may have been anywhere in your own development when you became a parent. There is no point in berating and blaming yourself now if you think with hindsight that you were not where you “should have been” when you got married, became a parent, and so on. The important questions are: where are you now, what is happening now, and where do you want to go from here? Spending time on any kind of blame just makes you ineffective and limits your energy for change. Blame is an expensive, useless, and destructive way to use your energy.

Most parents want their children to have lives at least as good as or better than they had. They hope they can be the means by which this happens. This makes parents feel useful and proud.

If you liked the way your father and mother brought you up and felt good about the way they treated each other, they can be quite acceptable models for your blueprint. You say, “I will do it the way they did it” and therefore also feel empowered to add whatever else seems to fit.

If you don’t like what happened as you grew up, you’ll probably want to change what you do. Unfortunately, deciding what not to do is only part of the story. We get very little direction from “what not to do.” You have to decide what you are going to do differently, and how you are going to do it. This is where the trouble starts: you are in a kind of no-man’s-land when you have no models to follow. You have to make up new ones. Where will you find them? What will you put into your new models?

Changing the models derived from one’s early past is often difficult. It is like breaking a long established habit. What we experienced in our childhood, day in and day out for years, is now a basic part of our life, whether it was comfortable or uncomfortable. I have heard parents lament, “I did not want to be like my mother and father, but I am turning out exactly like them.” This is an effect of modeling. What you experienced as a child became familiar. The power of the familiar is Very strong, often stronger than the wish to change. Strong interventions, lots of patience, and continual awareness help us challenge the power of the familiar.

Most people probably want their parenting to be different from the way they were parented. “I’m certainly going to bring up my kids different from the way I was brought up!” is a frequent refrain. It could mean anything from being more strict to less strict, being closer to one’s children to less close, doing more work or less work, and so on.

Now take a minute to remind yourself about those parts of what you saw and experienced in your growing up that you want to change with your children. What have you tried to do instead? How well is it working? Give yourself permission to find ways to make your changes work. Write down five family experiences that

were helpful to you. See if you can figure out what was helpful about them. Then find five experiences you felt were destructive and analyze them the same way. Have your spouse do the same thing.

Discuss and write down how you want to do things differently with your children. Share with your children what you want to have happen, and ask them to help you out. Remember how really wise you were as a child.

To go back to your family experience, you might, for example, remember how helpful it was when your mother told you directly and clearly what she wanted you to do rather than telling you indirectly. Maybe you remember how she looked directly at you, how she gently placed her hand on your shoulder, and how she spoke in a clear tone that was both firm and kind. “I want you to mow the lawn by five today.” This helped you feel good about mowing the lawn. By contrast, your father may have come home after work and yelled, “Why don’t you ever do anything around here? You’re going to get your allowance cut if you don’t watch out!” This made you afraid. You felt defensive.

You may remember that Grandma wasn’t very helpful because she always said “yes” no matter what you asked. Somehow you got to feeling too obliged to her. It wasn’t easy to be honest with Grandmother. Perhaps this memory will inspire you to teach your children to be honest in their responses.

You may have decided that Dad was very helpful when you took a problem to him. He would listen and then patiently help you struggle through finding a decision. This may have been in contrast to your uncle, who always solved your problems for you. Your uncle delayed your learning about finding your own two feet to stand on. Father was obviously more helpful to you.

You may have decided that neither parent was very helpful to you because whenever you interrupted them, they always stopped and put all their attention on you. This made you feel impossibly important. Later you felt hurt and confused when others didn’t treat you the same way. You had temper tantrums when you did not get what you wanted. Life was painful. You had not developed patience and an understanding that sometimes you have to wait your turn.

A destructive experience for you might have been when you said a “dirty” word, and your mother washed out your mouth with soap or put you in the closet. Your body ached from fear, and then you plotted revenge. Later you cried because you felt so unloved and abandoned.

When you have made your list, go another step and decide how you can use what you are learning in ways to fit your situation.

Take your “destructive list” and try to figure out what your parents may have been trying to teach you. With your adult eyes you might be able to see what you couldn’t see then. Chances are that you will want to teach your child some of the same things, only now you might be able to find a more constructive way to do it. For instance, is there a better way to respond to a child’s use of a dirty word than washing his mouth out with soap or sticking him in a closet? Can you find it?

You may discover that some of the things your parents taught you turned out to be factually wrong. For example, before Columbus proved otherwise, parents taught their kids that the world was flat. When we learned the world was round, this was no longer accurate information. Another example might be the idea that masturbating will make you crazy. There actually was a time when even physicians believed that masturbation led to insanity. Almost everyone today knows this is not so. Thoughts about masturbating may disturb some people, but the act itself is harmless.

In the 1940s parents were advised to feed babies on a strict schedule with no deviations. We now know this was injurious to the child. The important point is to become aware of these kinds of untruths and learn the current truth. This is not always easy either, as there are so many “truths” around. We need to develop ways to judge what is truth and what isn’t. Advertising and propaganda work on our emotions and sometimes conceal facts.

New parents have much to learn. For instance, many adults are ignorant as to how the human body grows. Many people are unfamiliar with the whole psychology of emotions and how emotions affect behavior and intelligence. Learning about how children develop is important information. Good information helps give you a sense of security.

Somehow or other, we have been a long time seeing that knowledge is an important tool for peoplemaking. We see it in the raising of pigs; however, it has been slow in relation to raising children. In some way, we got the idea that raising families was all instinct and intent. We behave as if anyone could be an effective parent simply by wanting to be, or because she and he just happened to go through the acts of conception and birth. Parenting is the most complicated job in the world. It is true that all of us are equipped with an inner wisdom. However, to be helpful, that knowledge has to be trapped.

We also need to accept coaching. Parents need all the help, knowledge, and support that is available. I think every community could benefit by having a parenting center that

met these needs. Maybe one of the readers of this book will

want to start such a service. It might include a cuddle room

for parents, where they could get a lot of TLC. So much is

asked of parents, and so little is given.

Guiding a baby to full humanness involves knowing

special things. Let’s examine the beginning of a family. This

starts when a couple has a baby. Now there are three where

two once were.

The coming of the child, even though wanted, requires major adjustments in the couple’s life. Shifts and changes in regard to time and presence with each other are essential to

accommodate the immediacy of the infant’s needs. People

who have already worked out a healthy balance in their relationship can handle this adjustment more easily. For parents who are not at that place, these changes may appear as maladjustments and take the form of physical or emotional stress, or both.

When these stresses appear, I have the following suggestions for the parenting pair.

1. Get someone you trust to look after your infant and find

a cozy, neutral place outside your home where you can

talk frankly and forthrightly with each other. Spend

time sharing what each of you is feeling, including your

resentments and disappointments, and your feelings of

helplessness and fear. Chances are that when this situation has arisen, the dream you have had with each other

seems to be fading. The baby has taken over. This time

can be especially hard for fathers, who don’t have all a

mother’s obvious linkage to the child. Fathers need to

know they are needed, wanted, and are essential. Women have the psychological authority to grant this place to

the fathers.

2. Put words to what you mean to each other, and what

your hopes are for and with each other. This will enable

you to renew your self-worth enough to join your energies and cope more positively with each other and your child.

Out of this frank talk, you may commit yourself to

some connecting time each day, and also something special for the two of you each week. Keeping your connection and making it a priority are basic steps toward fulfillment as parents. This needs to be a firm commitment and needs to be adhered to consciously.

What may further emerge is a fear of losing autonomy. “Where is some time for me?” is often an unspoken question. Couples need consciously to arrange time for each self. To make this work, verbalize your need and

then ask for the cooperation of your partner (and, later, of

other family members). Chances are good that something

can be worked out, but you have to ask for and plan it.

3. Center yourself enough to tap into your own internal

wisdom and see if you are working at cross-purposes

with yourself or each other. If so, pinpoint where the difficulty seems to be. Your internal wisdom is also a good

resource for new ideas about coping.

Most people will get farther by thinking of this crisis as

a challenge, rather than a failure of some sort. I recommend

approaching this in much the same way as a puzzle. How

can two people who care about each other use their energy

to team up and make things work in the interest of themselves, each other, and their child or children?

It is wise to remember that we have intelligence. Our intelligence works best when we are centered emotionally.

If none of the above work, I urge you to seek professional help.

All too often parenting becomes weighty and demanding, and life as a couple fades into the background. If this

happens and goes unattended, the child will pay a heavy

price. The child may be used as a reason for the couple to

stay together; or the couple may project their difficulties on

the child, overtly or covertly: “If it had not been for you,

things would be better.”

This can also be a time when one partner develops an emotional attachment with someone outside the marriage. This is often true of fathers who feel replaced by the child in the mother’s affections.

_Stop a moment and take stock. Is this happening with you?

With your spouse? What effect is this having on all the family

members? What are you willing to do or change now? Remember,

the reason you got married and became a parent was to extend the

joy in your life._

People often get discouraged because so much of what

they have tried hasn’t worked. Your willingness to admit

this frankly could be a turning point for you. You can learn

to do things differently, no matter how long things have been going wrong. We are only as far away from change as we are from really changing our minds and giving ourselves permission to go in new directions.

First, you have to find out what is happening and what

you have to learn. Then search for a way to learn it. Someone whose name I have forgotten said, “Life is your current view of things.” Change your view, and you change your

life. I heard about a man who always complained that everywhere he went, it was dark. This all changed one day when

he lost his balance; in falling, his glasses flew off. Lo and

behold, it was light! He hadn’t known he’d been wearing

dark glasses.

met these needs. Maybe one of the readers of this book will

want to start such a service. It might include a cuddle room

for parents, where they could get a lot of TLC. So much is

asked of parents, and so little is given.

Guiding a baby to full humanness involves knowing

special things. Let’s examine the beginning of a family. This

starts when a couple has a baby. Now there are three where

two once were.

The coming of the child, even though wanted, requires major adjustments in the couple’s life. Shifts and changes in regard to time and presence with each other are essential to

accommodate the immediacy of the infant’s needs. People

who have already worked out a healthy balance in their relationship can handle this adjustment more easily. For parents who are not at that place, these changes may appear as maladjustments and take the form of physical or emotional stress, or both.

When these stresses appear, I have the following suggestions for the parenting pair.

1. Get someone you trust to look after your infant and find

a cozy, neutral place outside your home where you can

talk frankly and forthrightly with each other. Spend

time sharing what each of you is feeling, including your

resentments and disappointments, and your feelings of

helplessness and fear. Chances are that when this situation has arisen, the dream you have had with each other

seems to be fading. The baby has taken over. This time

can be especially hard for fathers, who don’t have all a

mother’s obvious linkage to the child. Fathers need to

know they are needed, wanted, and are essential. Women have the psychological authority to grant this place to

the fathers.

2. Put words to what you mean to each other, and what

your hopes are for and with each other. This will enable

you to renew your self-worth enough to join your energies and cope more positively with each other and your child.

Out of this frank talk, you may commit yourself to

some connecting time each day, and also something special for the two of you each week. Keeping your connection and making it a priority are basic steps toward fulfillment as parents. This needs to be a firm commitment and needs to be adhered to consciously.

What may further emerge is a fear of losing autonomy. “Where is some time for me?” is often an unspoken question. Couples need consciously to arrange time for each self. To make this work, verbalize your need and

then ask for the cooperation of your partner (and, later, of

other family members). Chances are good that something

can be worked out, but you have to ask for and plan it.

3. Center yourself enough to tap into your own internal

wisdom and see if you are working at cross-purposes

with yourself or each other. If so, pinpoint where the difficulty seems to be. Your internal wisdom is also a good

resource for new ideas about coping.

Most people will get farther by thinking of this crisis as

a challenge, rather than a failure of some sort. I recommend

approaching this in much the same way as a puzzle. How

can two people who care about each other use their energy

to team up and make things work in the interest of themselves, each other, and their child or children?

It is wise to remember that we have intelligence. Our intelligence works best when we are centered emotionally.

If none of the above work, I urge you to seek professional help.

All too often parenting becomes weighty and demanding, and life as a couple fades into the background. If this

happens and goes unattended, the child will pay a heavy

price. The child may be used as a reason for the couple to

stay together; or the couple may project their difficulties on

the child, overtly or covertly: “If it had not been for you,

things would be better.”

This can also be a time when one partner develops an emotional attachment with someone outside the marriage. This is often true of fathers who feel replaced by the child in the mother’s affections.

_Stop a moment and take stock. Is this happening with you?

With your spouse? What effect is this having on all the family

members? What are you willing to do or change now? Remember,

the reason you got married and became a parent was to extend the

joy in your life._

People often get discouraged because so much of what

they have tried hasn’t worked. Your willingness to admit

this frankly could be a turning point for you. You can learn

to do things differently, no matter how long things have been going wrong. We are only as far away from change as we are from really changing our minds and giving ourselves permission to go in new directions.

First, you have to find out what is happening and what

you have to learn. Then search for a way to learn it. Someone whose name I have forgotten said, “Life is your current view of things.” Change your view, and you change your

life. I heard about a man who always complained that everywhere he went, it was dark. This all changed one day when

he lost his balance; in falling, his glasses flew off. Lo and

behold, it was light! He hadn’t known he’d been wearing

dark glasses.

How many of us are wearing the dark glasses of ignorance without knowing it? sometimes it takes a crisis to discover this. If we can get introduced to our ignorance, isn’t that something worth celebrating?

If you discover something going wrong in your family, treat it as you would when a red light in your car indicates that something isn’t working right. Stop, investigate, share your observations, and see what can be done. If you can’t change it, find someone you can trust who can. Whatever you do, don’t waste your time moaning about “poor me” and “bad you.”

Do what we talked about in the chapter on systems. Turn the family into a “research team” instead of a “blame society.” Can you see how different things might be for your family if you take the negative, hurtful things that happen as signals for attention? There is no need to blame and tear your hair out. Keep your hair and be glad you finally got the signal, whatever it is. It may not be especially pleasant, but it is honest and real, and something can be done about it. Don’t wait.

I remember a family I treated once. The father came with his wife and twenty-two-year-old son, who was quite ill psychologically. The red light had been on for some time before they took action. When the treatment was finished, the father, with tears in his eyes, put his hand on the son’s shoulder and said, “Thank you, son, for getting sick, so I could get well.” I still get goose bumps when I think about that one.

We can get into some traps unconsciously by using how we were patented as a guide to how we parent. One of these traps involves giving the child what the parent did not have growing up. The parent’s efforts can come out very well, but they can also end in terrible disappointment.

I once saw a vivid example of this. It was just after Christmas, when a young mother whom I will call Elaine came to see me. She was in a rage at her six-year-old daughter, Pam. Elaine had scrimped and saved many months to buy Pam a very fancy doll. Pam reacted with indifference; Elaine felt crushed and disappointed. Outside, she acted angry.

With my help, she soon realized that this doll really was the doll she had yearned for as a youngster and had never had. She was giving her daughter what was really her own unfulfilled dream doll. She expected Pam to react as she, Elaine, would have reacted when she was six. She had overlooked that her daughter already had several dolls. Pam would much rather have had a sled so she could go sliding with her brothers.

The doll was really Elaine’s. I suggested that she claim her own doll and experience her own fulfillment, which she did. This particular yearning from her childhood was satisfied directly, and she did not have to do it through her child. Instead, she bought Pam a sled.

Is there any good reason why adults cannot openly fulfill, in adulthood, some of the unfulfilled yearnings of their childhood? Oftentimes, if they don’t, they pass off these old needs on their kids. Children rarely appreciate passed-off satisfaction (unless they have learned how to act like yes-persons). Nor do they like parental strings on their gifts. I am thinking of fathers who buy trains for sons or daughters and then play with the toys all the time, setting out strict conditions under which the children can use their own trains. How much more honest it would be for the father to buy the train for himself. It would be his train, and he then might or might not allow his children to play with it.

What lingers from the parent’s individual past, unresolved or incomplete, often becomes part of her or his irrational parenting. I refer to this as the contaminating shadows of the past, of which many parents are totally ignorant. Another trap is when parents start out with a dream about what they want their child to be. This dream often involves wanting the child to do what they personally could not do, as in, “I want him to be a musician. I always loved music.” Many children have pinioned themselves on an altar of sacrifice so their parents would not be disappointed.

It is easy for parents, without knowing it, to make plans for their child to be what would fit the parents but not necessarily the child. I once heard the late Abraham Maslow say that having these kinds of hopes and plans for your children is like putting them into invisible straitjackets.

I see the results of this in adults who say they wanted to be something else but did not know how to deal with pressures from their parents. After all, it takes a lot of guts and know-how on the part of the child to defy parents successfully,especially when a lot of love is present.

There is another hurdle if you, as a parent, are shackled to your own parents. You may not feel free to parent your own child differently for fear of being criticized by your parents. This could easily result in your dealing "crookedly" with your child. Some quite insidious situations can develop. I refer to this as fettered parental hands.

For instance, I know a thirty-four-year-old father, jack, who won’t chastise his child directly because his father would take the child’s side. Then Jack and his father would argue. He is still afraid to argue with his father, because he fears his father’s rejection. The effect, of course, is that Jack deals inappropriately with his child. The ideas in his blueprint don’t match what he does. Were he to give a lecture on the best way to raise kids, his speech would be far different from what he practices.

I want to talk now about something I call the parental cloak (parental role). As I use the term, it refers to that part of the adult that lives out the role of a parent. To my mind, the parental cloak has a use only as long as the children are unable to do for themselves and need parental guidance. One of the problems is that the cloak may get stuck on the person, never changing, and stay forever. Once a mother, always a mother, even if the kids are already adults.

A major factor in one’s blueprint is the kind of parental cloak you wear, and whether you feel you have to wear it all the time. Can you take it off when you are not parenting? After all, sometimes you may want to “spouse” or “self” and you would then look peculiar wearing the parental cloak.

The parental cloak has three major linings: the “boss” lining, the “leader and guide” lining, and the “pal” lining. For some people, the cloak has no lining at all: there is no evidence of any kind of parenting. I think there are far fewer of these cloaks than the others.

The boss has three main faces. First is the tyrant, who flaunts power, knows everything, and parades as a paragon of virtue (“I am the authority; you do what I say”). This parent comes off as a blamer and controls through fear. The boss’s second face is the martyr, who wants absolutely nothing except to serve others. The martyr goes to great lengths to appear of little value and comes off as a placater. Control is managed through guilt (“Never mind me, just be happy”). The third is the great stone face who lectures incessantly, impassively, on all the right things (“This is the right way”). This person comes off as a computer. Control is managed through erudition and the consequent implication that someone is stupid, and it probably is “you.”

The pal is the playmate who indulges and excuses regardless of the consequences. This parent usually comes off irrelevantly (“I couldn’t help it——I didn’t mean to”). Children need pals for parents like they need the proverbial hole in their heads. Irresponsibility in children is a frequent outgrowth of this kind of parental cloak lining.

I think we pay a heavy price for some of the ways parents use their power, their cloak linings. To me, one very destructive lining is that of the tyrant, who insists on creating obedient and conforming human beings. In every case, I have found that such behavior was primarily the result of an adult who tried to hide uncertainty by getting immediate obedience from a child even if it were inappropriate. How else would the uncertain parents know they were effective?

Many parents might occasionally entertain a momentary wish to knock in their kid’s head, but few do it. Many children feel similarly toward their parents, but only a few act on those feelings. These feelings represent the ultimate in frustration.

It is rare that children who grow up on the obedience frame become other than tyrants, or victims, unless some unusual intervention occurs in their lives. The obedience theme is, roughly, “There is only one right way to do anything. Naturally, it is my way.” It is beyond me how anyone can think that good judgment can be taught through “obey me” techniques. If we need any one thing in the world, it is people with judgment. The person who cannot use common sense is the person who feels he or she must do what somebody else wants or expects.

I heard about “the right way” so much that I investigated how many ways there were to wash dishes. I found 247, all of them going from dishes in the state of being dirty to that of becoming clean. The differences were related to the kind of equipment available, and so on. Do you know anybody who swears by a certain detergent? Or swears that dishes must always be rinsed before being washed? After you have been around a person who insists on the “right” way all the time, you probably want to kill him or her. Maybe it’s no accident that over 80 percent of all murders are of family members. (I did not say that 80 percent of families murder each other.)

People who are around a tyrant——someone who says, “You do it because I say so,” or “It is so because I say so”—— suffer personal insult constantly. It is as though the other person were saying, “You are a dummy. I know best.” Such statements have long-range crippling effects on morale.

In none of these parental cloaks can parents develop a trusting atmosphere with their children. Effective learning cannot occur in an atmosphere of distrust, fear, indifference, or intimidation.

My recommendation is that parents strive to be empowering leaders. This means being kind, firm, inspiring, understanding people who direct from a position of reality and love rather than negative use of power.

People play cruel tricks on themselves when they become parents. Suddenly now they must “do their duty,” be serious, and give up lightness and joy. They can no longer indulge themselves or even have fun. I happen to believe just the opposite. People who believe that family members can be enjoyed and appreciated as real also see normal, everyday difficulties in families in quite a different light.

I remember a pair of young parents, Laurie and josh, who told me their first priority was to enjoy their child. They were obviously already enjoying each other. Through enjoying their child, they were teaching their child to enjoy them. The enjoyment still goes on today, fifteen years and two other children later. I feel good every time I am around this family. Growth is obvious, and each takes pride in accomplishment and has good feelings about each other. These are not indulgent parents, nor is the family without secure and clearly set limits. Clear "no's" as well as "yes's" are considered healthy words in this family and are used honestly and appropriately.

Part of the art of enjoyment is being flexible, curious, and having a sense of humor. An episode of a five-year-old spilling milk can be a different experience depending on what family the child lives in and how such matters are approached. There is no universal way of treating that.

My friends Laurie and Josh would probably say to Davis, their child, “Whoops! You let your glass be your boss instead of your hand! You will have to talk with your hand. Let's skip out to the kitchen and get a sponge and soak it up." Literally, then, Laurie or Josh would skip out to the kitchen with Davis and maybe even sing a song on the way back.

I can hear Josh saying, "Gee, Davis, I remember when that happened to me. I felt I had done something awful, and I felt terrible. How do you feel?" To which Davis would answer, "I feel bad, too. Now there's more work to do to clean up the mess. I didn’t mean to do it." It would be a normal feeling of apology and not an assault on self-worth.

I can imagine the same episode with another set of parents, Al and Ethel. Ethel grabs Davis, shakes him, and demands that he leave the table, saying to Al as he leaves, “I don’t know what I’m going to do with that kid. He’s going to grow up to be a slob.”

Another pair I know, Edith and Henry, would have still another scene. When the milk is spilled, Henry looks at Edith, raises his eyebrows, and goes on eating in stony silence. Edith quietly gets a sponge and wipes up the milk, giving Davis a reproving look when she catches his eye.

I believe Laurie and Josh approached the happening in a way that benefits everyone. The other two examples do not. What do you think? Can you imagine basing your response to negative situations on the premise that what is happening is happening between people who have good will and love toward each other? And that therefore education and good humor, not punishment, are needed? How do you approach these kinds of events in your family?

Do people in your family have times when they obviously enjoy each other as individuals? If you think not, see if you can find out how to change that. People who cannot enjoy each other probably have put obstacles in the way of loving each other as well.

A big part of a child’s joy in him- or herself is learned from being encouraged to enjoy parts of the body, the feel of skin, touching, colors, and sounds——especially the sound of the child’s own voice, together with the pleasure of looking. Parents show the way through their joy in the child. Laughter and love are catching.

Enjoyment is also a matter of aesthetics. Relatively speaking, we do very little in our customary child-rearing practices to help children consciously learn to enjoy themselves. I see many families whose whole idea of raising children and being parents is a grim experience full of labored work, hysteria, and burden. I’ve noticed that once adults lose their blocks against enjoying themselves, life seems easier on all fronts. They are lighter and more flexible with their children and themselves. I don’t know if you are aware of how much heaviness and grimness exist among adults. I am not surprised to hear numbers of children tell me they don’t really want to grow up because being an adult is no fun.

I don’t think having fun or using humor takes away from being competent or responsible. As a matter of fact, I think real competence includes enjoying oneself, one’s working partners, and what one is doing. At a recent conference, I learned that a large, successful corporation has three new criteria for selecting personnel: they are looking for candidates who are kind, fun to be around, and competent. Since these qualities are appreciated by everyone, let us make them goals for our child-rearing and for our own lives.

Learning how to laugh at yourself and see a joke on yourself is very important. Having these attributes may make the difference, in the future, in whether you get hired. Our learning and practice of this skill come from the family. If we have to take everything Father says and Mother says (or does) as though it were the ultimate wisdom and power, we have little opportunity to develop the fun side of things. I’ve been in some homes where the grimness and the seriousness hung like an impending storm in the air——where politeness was so thick that I had the feeling only ghosts lived there, not people. In other homes everything was so clean and so orderly that I felt as if I should be an especially sterilized towel from the laundry. I would not expect enjoyment of people to develop in either of these atmospheres.

What kind of an atmosphere do you have in your family? Can you believe that laughter and fun nurture the body?

We are just beginning to understand and hold seminars on how laughter and humor provide healing and nurture for the body. We have known for a long time how worry, fear, resentment, and other negative emotions have destructive results. Laughter and love are good medicine. They cost nothing but awareness. I believe that I do my most definitive and serious work when the atmosphere is light. And Josh and Laurie’s treatment of their child’s milk spilling helped him learn more than those approaches that involved punishment and disapproval.

What can you put into your blueprint to encourage laughter, enjoyment, and humor?

Like enjoyment, loving is a very important part of life. Did you ever stop to realize what a feeling of loving is like? When I feel loving, my body feels light, my energy flow seems freer, I feel exhilarated, open, unafraid, trusting, and safe. I feel an increased sense of my own worth and desirability. I have a heightened awareness of the needs and wishes of the person toward whom I direct these feelings. My desire goes toward a joining of those needs and wishes with my own. I don’t want to injure or impose on the one I love. I want to join with her or him, to share ideas, to touch and be touched, to look and be looked at, and to enjoy and be enjoyed. I like the feeling of loving. I consider it the highest form of expressing my humanness.

I find the manifestation of love a scarce commodity in many families. I hear much about the pain, frustration, disappointment, and anger that family members feel for one another. When people give so much attention to these negative feelings, their other positive feelings shrivel from being unnoticed.

I am in no way proposing that life does not have its hazards and corresponding negative actions and feelings. I am saying that if those are all we focus on, we miss opportunities to see what else is there. Hope and love are what keep us going forward. If we spend too much time focusing on doing the “right” things and getting the work done, we of- ten have little time for loving and enjoying one another. We discover this at funerals or when it is too late.

All right. We’ve talked about some of the challenges of parenting. Perhaps you are beginning to see more ways to help you draft a stronger, more vital blueprint for your family.

I am reminded at this point of classic Robert Benchley story. When Benchley was a college student, one of his final examinations was to write an essay on fish hatcheries.

He hadn’t cracked a book all semester. Undaunted, he started his final something like this: “Much wordage has been devoted to fish hatcheries. No one, however, has ever covered this subject from the point of View of the fish.” And thus he proceeded to create what is probably the most entertaining final in Harvard’s history.

Having devoted all these pages to parenting, we are now going to take a look at the family situation from the point of view of the baby.

I am going to imagine being inside a baby called Joe, somewhere around the age of two weeks.

“I feel my body hurting me from time to time. My back hurts when I am tucked in too tight, and I have to lie too long in one position. My stomach gets tight when I am hungry or hurts when I get too full. When the light shines directly in my eyes, it hurts them because I can’t move my head yet to turn away.

“Sometimes I am in the sun, and I am burning. My skin is hot sometimes from too many clothes and sometimes cold from too few clothes. Sometimes my eyes ache and I get bored from looking at a blank wall. My arm goes to sleep when it is tucked under my body too long. Sometimes my buttocks and my crotch get sore from being wet too long. Sometimes my stomach cramps when I am constipated. When I am in the wind too long, it makes my skin prickle.

“Sometimes everything is so still that my body feels dry and uncomfortable. My body hurts when my bath water is too cold or too hot.

“I get touched by many hands. I hurt if those hands are gripping tightly. I feel clutched and squeezed. Sometimes those hands feel like needles. Sometimes they are so limp that I feel I am going to fall. These hands do all kinds of things: push me, pull me, support me. These hands feel very good when they seem to know what I feel like. They feel strong, gentle, and loving.

“It is really painful when I get picked up by one arm, or when my ankles are held together too tightly when my diaper is changed. Sometimes I feel that I am suffocating when I am held so close to another person that I can’t breathe.

“One terrible thing is when someone comes to my crib and suddenly puts that big face over mine. I feel that a giant

is going to stamp me out. All my muscles get tight, and I hurt. Whenever I hurt, I cry. That is all I have to let anyone know that I am hurting. People don’t always know what I mean.

“Sometimes the sounds around me make me feel good.

Sometimes they hurt my ears and give me a headache. I cry then, too. Sometimes my nose smells such lovely things, and sometimes smells make me sick. That makes me cry.

“Much of the time my mother or father notice me when I cry. It is so good when they know I am hurting and they find out what hurts me. They think of pins sticking me, my stomach needing food, or that I am constipated or lonely. They pick me up, rock me, feed me, jiggle me. I know they want me to feel better.

“It is hard because we don’t speak the same language. Sometimes I get the impression that they just want to shut me up and get on with something else. They jiggle me for a short time as if I were a bag of groceries, and then leave me. I feel worse than before. I guess they have other things to do. Sometimes I guess I must annoy them. I really do not mean to do that. I don’t have any good ways to tell them what is wrong.

“My body hurts seem to go away when people touch me as if they like me. They seem to feel good about themselves, and I know they are really trying to understand me. I try to help as much as I can. I try to make my cries sound different. It also feels good when someone’s voice is full, soft, musical. It feels good when my mother and father really look at me, especially into my eyes.

“I don’t think that my mother knows when her hands are painful to me and her voice so harsh. I think if she knew, she would try to change. She seems so distracted at those times. When my mother’s hands feel painful many times in a row and her voice stays unpleasant, I begin to get afraid of her. When she comes around, I stiffen and pull back. She then looks hurt or sometimes angry. She thinks I don’t like her, but I am really afraid of her. Sometimes my father is gentler and I feel warm and safe with him. When my father feels good, I feel relaxed.

“Sometimes I think my mother doesn’t know that my body reacts just like hers. I wish I could tell her. Some of the things she says about me and the rest of the family when I am in my crib and she is with her friends, I don’t think she would say if she knew that I have perfectly good ears. I remember once hearing her say, ‘Joe will probably be like Uncle Jim,’ and she started to cry. There were other similar things that happened, and I began to feel that something terrible was wrong with me.”

[Years later, I find out that Uncle Jim was my mother’s favorite brother and must have been a great guy. I have often heard my mother say how much I looked like him. She cried because he died in an automobile accident in which she was driving. That put a whole different light on things for me; however, I did not know this for years. I think if she had told me about her love feelings for Jim and how bad she felt about his death, particularly since I seemed to be like him in ways, I would have not felt so bad! I would have understood that when she looked at me and started to cry, she was remembering him.]

It is important for adults to tell children, no matter how young or old, what they are thinking and feeling. It is so easy for a child to read the wrong message.

“Since being born, I have spent most of my time on my back, so I’ve gotten acquainted with people from this position. I know more about my mother’s and father’s chins from underneath than almost anything else. When I am on my back, I see things that are mostly up and above me; and of course, I see them from underneath. This is how things are in the world.”

Now I’ll imagine Joe’s perspective as he grows:

“I was very surprised to see how much things had changed when I learned to sit up. When I began to crawl, I saw things underneath me, and I really got acquainted with feet and ankles. When I started to stand up, I began to know a lot about knees. When I first learned to stand up, I was only about two feet tall. When I looked up, I saw my mother’s chin differently. Her hands looked so big. In fact, a lot of times when I stood up between my mother and father, they really seemed far away and sometimes very dangerous, and I felt very, very little.

“After I had learned to walk, I remember going to the grocery store with my mother. She was in a hurry. She had hold of one of my arms. She walked so fast that my feet hardly touched the ground. My arm began to hurt. I started to cry. She got angry with me. I don’t think she ever knew why I was crying. Her arm was hanging down, and she was walking on two feet; my arm was pulled up, and I was hardly on one foot. I kept losing my balance. I feel uncomfortable and sometimes dizzy when I lose my balance.

“I remember how tired my arms used to get when I would walk with my mother and father when each had hold of one arm. My father was taller than my mother. I had to reach higher for his hand. So I was kind of lopsided. Half the time I did not have my feet on the ground. The steps that my father took were very big. When my feet were on the ground, I tried to keep up with him. Finally, when I couldn’t stand it anymore, I begged for my father to carry me. He did. I guess he thought I was just tired. He didn’t know that I was contorted so badly that my breathing was even getting hard. There were very nice times, but somehow the bad times stayed with me longer.

“My mother and father must have gone to a seminar some place because they changed. Whenever they wanted to talk to me after that, they would always stand me on something so they could look at me at eye level and then they would gently touch me. That was so much better.”

I try to contact all children at eye level. That usually means that I have to squat when I contact them, or have them stand on something to equalize our heights.

Since first impressions make such an impact, I’ve wondered whether that first picture the infant has of an adult isn’t one of giantness, which automatically means great power and strength. This can feel like a great comfort and support, and also like a great danger compared to the littleness and helplessness of the child.

I’ve mentioned this before, but it’s important enough to bear a little repetition. When an adult first gets acquainted with her or his child, the child is, indeed, little and helpless. This could account for parents' image of their child as little and helpless, which can continue far beyond the time

when the condition exists. That is, the son or daughter, even at eighteen, is still a “child,” little and helpless in parents’ eyes, no matter how grown-up, powerful, and competent the adult child really is. In much the same way, the adult child could hang onto the image of parents as all-powerful even when she or he becomes powerful in his or her own right.

I think parents who are aware of this possibility help their child discover his or her own power as quickly as possible. They freely use themselves to show their child how to become powerful and what limits exist for that power. Without this learning, a child could become an adult who is a parasite on other people, dominates them, or plays god to them, benignly or malevolently.

Infants have all the physical responses that adults have. Their senses are in working order at birth (as long as it takes to clean out the orifices); therefore it makes sense that the infant is capable of feeling whatever an adult feels. Infants’ brains are working to interpret what they feel, even though they can’t tell anyone what sense they are making. Taking this view, it becomes easy to treat children as persons.

The human brain is a marvelous computer, constantly working to put things together and make sense of what comes to it. If the brain cannot make sense, it makes nonsense. Like the computer, the brain doesn’t know what it doesn’t know; it can use only what is already there.

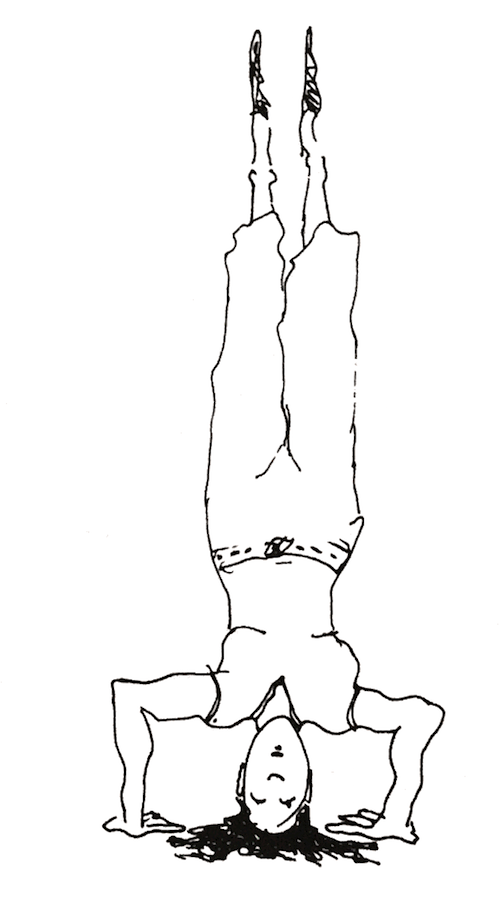

One of the things I do when I work with parents is the following exercise.

One adult is asked to become an infant in a crib, lying face up. Not yet old enough to speak, this person is asked to react only with sounds and simple movements. I then ask another pair of adults to bend over the baby, doing the things that babies need done for them, trying to follow the baby’s clues. In turns, each adult becomes the baby. After about five minutes in this role-playing situation, I ask each adult to tell the other two what he or she was feeling as this was going on.

In another round, I announce some outside interference, such as the telephone or doorbell ringing. I choose the time when the baby is obviously fussy, then watch to see what happens to the two parents and the child. Again, I ask the role-players to tell each other what difference the interruption made to them. Try this yourself.

This is a simple way to help adults appreciate what a baby might experience and how the child uses this experience to build expectations of others.

The touch of a human hand, the sound of a human voice, and the smells in the home are the experiences by which a baby begins learning what the new world is all about. How a parent touches and sounds to the child form the basis for what the child learns. The baby must unscramble all the touches, faces, voices, and smells of surrounding grown-ups and make meaning of them. The newborn’s world is a very confusing place.

I believe children already have some pretty clear expectations by the time they can feed themselves, walk, control their bowels and bladder. and talk. This is around the age of three. After that, children just develop variations. In this period, they learn how to treat themselves. how to treat others, what to expect from others, and how to treat the world of things around them. The family blueprint now becomes crucial: what do you teach and how do you teach it?

No learning is single-level. While children are learn- ing to use their legs in walking, they’re also learning something about how people perceive them and what is expected. From this, children learn about what to expect from others and how to deal with them. Babies also learn something about the world they are exploring and how to act in that world: “No, no! Don’t touch,” or “Touch this, doesn’t this feel good?”

In the first year of life, a child must learn more major and different things than in all the rest of her or his life put together. Never again will the child be faced with learning so much, on so many fronts, in so short a time.

The impact of all this learning is much deeper than most parents realize. If parents understood this, they would better appreciate the link between what they do and the tremendous job their child has to do. We have focused too much attention on disciplinary methods and not enough on understanding, loving, and humor, and developing the beautiful manifestation of life that resides in every child.

Three other areas complicate carrying out the blueprint. They are in the iceberg, below the perceivable functioning of the family. The first is ignorance. You simply don’t know something. Further, you may not know that you don’t know, so you wouldn’t be aware of the need to find out. Children can help a lot with this if the parent is open to children’s comments. Be alert to children’s hints for information.

The second is that your communication may be ineffective. You may be giving out messages you don’t know about, or you think you’re giving messages when you’re not; so the goodies you have to offer your children do not get across. Watching for unexpected reactions from others can alert you to this.

Many parents are amazed at what their children have taken from their apparently innocent statements. For example, I know a white couple who wanted to teach their child racial tolerance. Along with some other children, a little black child was a guest in their home one day. Later the father asked his child, “What did you think of his very curly hair?” But he said this in a way that pointed out the differentness, thus forging the first ring of distance between the two children. If parents are alert to the possibility of this kind of thing happening, they can monitor themselves now and then to see what their child has picked up.

I am reminded of another story. A young mother went through a rather lengthy presentation of the facts of life to her six-year-old son, Alex. Several days later, she noticed Alex looking at her very quizzically. When asked about it, Alex said, “Mommy, don’t you get awfully tired of standing on your head?” Completely baffled, she asked him to explain.

He said, “Well, you know, when Daddy puts the seed in.” His mother had neglected to embellish on the process of intercourse, so Alex filled in his own picture.

The third area in the iceberg has to do with your values. If you are uncertain of your own values, you can’t very well teach your child anything definite. What are you supposed to teach if you don’t know yourself? And, if you feel you can’t be straight about your problem, this situation could easily turn into “Do what I say, rather than what I do,” or, “It doesn’t really matter,” or, “Why ask me?” or, “Use your own judgment.” Any of these responses could leave your child with feelings about your unjustness or phoniness.

Another inadvertent message from a parent is shown in the following story. I was visiting a young woman who had a four-year-old daughter. The telephone rang. My young friend said, “No, I can’t come today. I’m not feeling well.”

Her four-year-old asked, with some concern on her face, “Mama, are you sick?”

My friend replied, “No, I’m just fine.”

The little girl attempted to deal with the apparent discrepancy: “But Mama, you told the lady on the telephone that you weren’t feeling well.”

Her mother’s reply was, “Don’t worry about it.”

With this, the little girl went out to play in her sandbox. At lunchtime, her mother called her inside. The little girl replied, “I can’t come, I am sick.”

Mother’s response was to go out to the sandbox, obviously angry, “I’ll teach you to disobey me.”

I intervened with the mother before she had a chance to chastise her child, and invited her to a private place to talk. I played back to her the chain of events, showing her that her child was simply imitating her. She saw the connection, to which she had been completely oblivious. She shuddered at how close she had come to misusing her child.

I suggested to the mother that a more useful way of coping with the original question might have been to say, “I am not sick. I told that woman that because I did not want to be with her and I did not want to hurt her feelings. It is hard for me to say ‘no’ to people. So I lie that way. I need to learn better ways of handling that. Maybe we can learn together.”

The mother was not a monster and the child was not a disobedient brat. Yet in this scenario the child could have been punished for learning and using something her mother modeled. The child would have had the necessary experience to begin distrusting her mother, and neither would have known why.

As I said before, the main data that goes into our family blueprints comes from experiences in our own families and those other families with whom we had intimate contact. All the people we called by a parental name, or whom we were obliged to treat as if they were parents, supplied us with experience that we are using in some way in our own parenting. Some of this may have been helpful to us, and some not. All of it had its effect, however.

Those of us who are free enough to contact our Inner Wisdom have another wonderful resource. It takes courage to trust that wisdom. It means we are free of judging, blaming, and placating; we are willing not only to level but to take risks.