6. Communication: Talking and listening

I see communication as a huge umbrella that covers and affects all that goes on between human beings. Once a human being has arrived on this earth, communication is the largest single factor determining what kinds of relationships she or he makes with others and what happens to each in the world. How we manage survival, how we develop intimacy, how productive we are, how we make sense, how we connect with our own divinity——all depend largely on our communication skills.

Communication has many facets. It is a gauge by which two people measure one another’s self-worth. It is also the tool by which the “pot level” can be changed. Communication covers the whole range of ways people pass information back and forth: it includes the information they give and receive, the ways that information is used, and how people make meaning out of this information.

All communication is learned. Every baby who comes into this world comes only with raw materials——no self-concept, no experience of interacting with others, and no experience in dealing with the world. Babies learn all these things through communication with the people who are in charge of them from birth on.

By the time we reach the age of five, we probably have had a billion experiences in sharing communication. By that age we have developed ideas about how we see ourselves, what we can expect from others, and what seems to be possible or impossible for us in the world. Unless something powerful changes those conclusions, that early learning becomes the foundation for the rest of our lives.

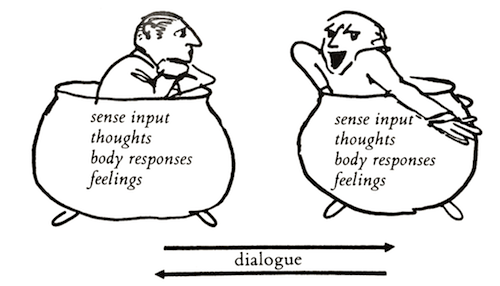

Once we realize all communication is learned, we can set about changing it if we want to. First, I want to review the elements of communication. At any point in time everyone brings the same elements to the communication process.

We bring our bodies——which move and have form and shape.

We bring our values——those concepts that represent each person’s way of trying to survive and live a “good” life (the oughts and shoulds for self and others).

We bring our expectations of the moment, gleaned from past experience.

We bring our sense organs——eyes, ears, nose, mouth, and skin, which enable us to see, hear, smell, taste, touch, and be touched.

We bring our ability to talk——words and voice.

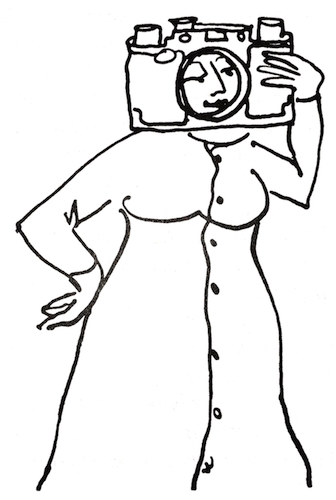

We bring our brains——the storehouses of our knowledge, including what we have learned from past experience, what we have read. and been taught, and what has been recorded in both hemispheres of our brains. We respond to communication like a film camera equipped with sound. The brain records pictures and sounds in the present, between you and me.

This is how it works. You are face to face with me. Your senses take in what I look like, how I sound, what I smell like, and, if you happen to touch me, how I feel to you. Your brain then reports what this means to you, calling on your past experience, particularly with your parents and other authority figures, your book learning, and your ability to use this information to explain the message from your senses. Depending on what your brain reports, you feel comfortable or uncomfortable; your body is loose or tight.

Meanwhile, I am going through something similar. I too see, hear, feel something, think something, have a past, and have values and expectations; and my body is doing something. You don’t really know what I am sensing, what I am feeling, what my past is, what my values are, or exactly what my body is doing. You have only guesses and fantasies, and I have the same about you. Unless the guesses and fantasies are checked out, they become the “facts” and as such can often lead to miscommunications and traps.

This is a picture of communication between two people.

To illustrate the sensory message, the brain’s interpretation of it, and the consequent feelings and feelings about the feelings, let’s consider the following. I am in your presence; you are a man. I think, “Your eyes are very wide apart, you must be a deep thinker”; or, “You have long hair, you must be a hippie.” To make sense out of what I see, drawing on my experience and knowledge, what I tell myself influences me to have certain feelings both about myself and about you before a word is spoken.

For example, if I tell myself you’re a hippie, and I’m afraid of hippies, then I might feel fear in myself and anger at you. I might get up and leave this frightening situation, or I might slug you. Then again, perhaps I would tell myself you look like a scholar. Since I admire smart people, and feel you are like me, I might want to start a conversation. On the other hand, if I felt myself to be stupid, your being a scholar might make me feel ashamed, so I would bend my head and feel humiliated. In other words, I make you up by how I interpret you. You can easily not know anything about how I am perceiving you. My responses to you might not make sense to you.

Meanwhile you are also taking me in and trying to make sense out of me. Perhaps you smell my perfume and decide I am a nightclub singer, which is offensive to you; so you turn your back. On the other hand, maybe my perfume would make you decide I am a neat gal, and you would search for ways to contact me. Again, all this takes place in a fraction of a second before anything is said.

With whom am I now having the pleasure, you or my picture of you?

I have developed a set of games or exercises that will help deepen your awareness and appreciation of communication. As with the rest of this chapter, these emphasize looking, listening, paying attention, getting understanding, and making meaning.

It is best to try these games with a partner. Choose any member of your family you wish. You will all learn and grow if you all take part. If no one wishes to join you, then try it alone in your imagination.

Sit directly in front your partner, close enough to be able to touch easily. You may not be used to doing what I’m going to ask you to do; it may even seem silly or uncomfortable. If you feel that way, try to go along anyway and see what happens. No one, as far as I know, has ever been even slightly damaged.

Now imagine you are two people, each with a camera, photographing the other. This is how it is when two people are face to face. Other people may be present, but only two people can be eye to eye at any moment in time.

A picture must be processed to see what actually was photographed. Human beings process their pictures in the brain, which interprets them; then action follows from that.

Now, to start the exercise. First, sit back comfortably in your chair and just look at the person in front of you. Forget what Mama and Papa said about its being impolite to stare. Give yourself the luxury of fully looking. Don’t talk while you are doing this. Notice each movable part of the face. See what the eyes, eyelids, eyebrows, nostrils, facial and neck muscles are doing, and how the skin is coloring. Is it turning pink, red, white, blue? You’ll observe the body, its size and form, and the clothing on it. And you’ll be able to see how the body is moving——what the legs and arms are doing, how the back is held.

Do this for about one minute and close your eyes. See how clearly you can bring this person’s face and body to your mind’s eye. If you’ve missed something, open your eyes and pick up on the details you may have overlooked.

This is the picture-taking process. Our brains could develop the picture as follows: “His hair is too long. He should sit up straight. He is just like his mother”; or, “I like her eyes. I like her hands. I don’t like the color of her dress. I don’t like her frown.” Or you may ask yourself, “Does he frown all the time? Why doesn’t he look at me more? Why is he wasting himself?” You may compare yourself to her. “I could never be as smart as she is.” You may remember old injuries: “He had an affair once; how can I trust him?”

This is part of your internal dialogue. Are you aware that dialogue of some kind is going on in your head all the time? When your senses are focused on something, this inner dialogue is emphasized.

As you become aware of your thoughts, you may notice some of them make you feel bad. You may also notice that your body responds. Your body may stiffen, your stomach get butterflies, your hands become sweaty, your knees weak, and your heart beat faster. You may get dizzy or blush. If, on the other hand, you’re having thoughts that make you feel good, your body may relax. Your thoughts and your body responses have strong influences on each other.

All right. We’re ready to go on with the exercise. You have really looked at your partner. Now close your eyes. Does she or he remind you of anyone? Almost everyone reminds one of someone else. It could be a parent, a former boy- or girlfriend, a movie star, a character in a fairy tale or literature——anybody. If you find a resemblance, let yourself be aware of how you feel about that other person. Chances are that the reminders are strong, you’ll sometimes get that person mixed up with the one in front of you. You could have been reacting to your partner or someone else. In this case, your partner will be in the dark and feel unreal about what is happening.

After about a minute, open your eyes and share what you’ve learned with your partner. If you found another person while your eyes were closed, tell your partner who it was, what part of him or her reminded you of your partner, and how you feel about this. Of course, your partner will do the same thing.

When this kind of thing happens outside this exercise context, communication is taking place with shadows from the past, not real people. I have actually found people who lived together for thirty years treating one another as someone else and constantly suffering disappointment as a result. “I am not your father!” finally cries the husband in a rage.

As mentioned, your responses to someone take place almost instantly. What words come out depend on how free you and your partner feel with one another, how sure you are about yourself, and how aware you are in expressing yourself. Let as much be said as is possible. Don’t push either yourself or your partner.

So you have looked at your partner, and you have become aware of what is going on inside you. Now, close your eyes for a minute. Let yourself become aware of what you were feeling and thinking as you looked: your body feelings and also how you felt about some of your thoughts and feelings. Imagine telling your partner all you can about your inner space activity. Does the very thought of it make you quake and feel scared? Are you excited? Do you dare? Put into words all you want to and/or can about your inner space activity, talking quietly and with a sharing attitude about what went on within you.

How much of your inner space activity were you willing to share with your partner? The answer to this question can give you a pretty good idea of where you stand in terms of freedom with your partner. If you quaked at the thought of sharing, you probably didn’t want to tell much. If you had negative feelings, you probably wanted to hide them. If there is very much of this negative kind of response, you’ve probably been troubled about your relationship. If you felt you had to be careful, could you let yourself know why? Could you be honest and direct?

Here is another important exercise related to the one you have just finished. I call it bringing yourself up to date.

All family members have a history with each other. Sometimes things have occurred in the past that never got talked about, leaving old hurts and fantasies still around. Something in us human beings seeks closure of unfinished business.

Give yourself permission to finish unfinished business. Having done that, you can bring yourself up to date with each family member and start out on a clean slate. Old unfinished business is often a barrier to full acceptance in relationships. Get in the habit of doing the following when the need arises.

Invite one family member to join you. Remember this is not a confrontation. It is more like closing the books on an old subject, with understanding. If your invitation is accepted, choose a comfortable place to sit, position yourself at eye level, calm yourself and breathe consciously. Now, tell your family member that there are some things you would like to clear up, make straight, or close. Perhaps all you will have to do to finish is put words to what this is. In some cases more will be required: for example, your unfinished business includes assumptions, you may want to ask some questions.

The dialogue might go something like this. “Two weeks ago Monday, I told you that I would go for a walk with you. I didn’t do it. I forgot. I want you to know that I want to work on keeping my promises.” Or, “Last night I felt angry when you chose someone else, rather than me. I don't feel angry anymore. Could you tell me why you did not choose me?” Or, “I feel so proud of your performance at the concert yesterday. I guess I was feeling a little jealous and I did not tell you.”

Many families have told me this keeping-up-to-date exercise has prevented many possible rifts, healed rifts that exist, deepened bonds between family members, and has led to more understanding of each other.

When you have finished what you wanted to say, invite your family member to share his or her feelings and any further thoughts on the matter. Close the exercise with a thank-you and a sharing of your feelings now that things are resolved.

It is important to remember that any invitation is open to acceptance as well as rejection. If the family member you ask does not accept your invitation, thank that person for at least hearing you and wait for another time.

Having done exercises about the picture-taking process, now we are ready for the sound part of your camera to become active. When your partner starts breathing heavily, coughing, making sounds, or talking, your ears report it to you. Your hearing stimulates past inner space experience just as seeing does.

Listening to another person’s voice usually puts other sounds in the background. The voice may be loud, soft,

high, low, clear, muffled, slow, or fast. Again, you have thoughts and feelings about what you hear. You notice and react to voice quality——sometimes to the extent that the words may escape you and you have to ask your partner to repeat them.

I’m convinced few people would talk as they do if they knew how they sounded. Voices are like musical instruments: they can be in or out of tune. Since the tunes of our voices are not born with us, we have hope. If people could really hear themselves, they might change their voices. I am convinced most people don’t hear how they really sound but only how they intend to sound.

Once a woman and her son were in my office. She was saying in loud tones to him, “You are always yelling!” The son answered quietly, “You are yelling now.” The woman denied it. I happened to have my tape recorder on, and I asked her to listen to herself. Afterwards she said rather soberly, “My goodness, that woman sounded loud!”

She was unaware of how her voice sounded while she was talking; she was aware only of her thoughts, which were not getting over because her voice drowned them out. You all probably have been around people whose voices were high-pitched and harsh, or low and barely audible, or who talked as if they had a mouthful of mush; and you have experienced the resultant injury to your ears. A person’s voice can help you or hinder you in understanding the meaning of her or his words.

Share with your partner how her voice sounds to you, and ask her to do the same.

When more of us know how to hear our voices, I think they will change considerably. Listen to yourself on a tape recorder; prepare yourself for a surprise. If you listen to it in the presence of others, you will probably be the only one who feels your recorded voice sounds different. Everyone else will say it’s right on. Nothing is wrong with the tape recorder.

Now let us go farther in exploring communication. This time it will have to do with touch. To help you find the next exercises more meaningful, consider what I am about to tell you about touch.

Just as breath is our link to life, touch is the most telling means of conveying emotional information between two people. Our most concrete introduction to this world was through the touch of human hands, and touch remains the most trusted connection between people. I will believe your touch before I believe your words. Intimate relationships are turned on or off by the way people experience touch.

Remind yourself of how many ways you use your hands: to lift, to caress, to hold, to slap, to balance. Every touch has a feeling connected with it, including love, trust, fear, weakness, excitement, and boredom.

I teach people to become aware of what their touch feels like to someone else. The way to do this is to ask, “How do you feel when I touch you as I do?” We have very little training in learning to feel our touch. For many people, the above question might seem awkward. After you try it for awhile, you can see its value.

Another part of touching consists of telling someone else how his or her touch feels to you. It is important to remember that until someone calls our attention to it, many of us are unaware of what our touch feels like. I am reminded of the many times loving, enthusiastic people have left blood in my hands: I was wearing rings when they were squeezing my fingers in a hearty handshake.

I believe also that most parents never intend to injure their children when they hit them. They are altogether unaware of the power of their slap. Many parents are horror stricken when they see the results of what they have done. This applies particularly to individuals who are taught to be physically strong without being taught to be aware of their effect on other people, especially children.

I knew a police officer who broke three of his wife’s ribs when he was hugging her after a period of absence. I know this man had no hostile feelings toward his wife. He just had no idea of his strength.

I want to emphasize that we need to learn to feel our touch as well as think it. This part of our education has been neglected for most of us. We can change this if we take our courage to ask, “How do you feel when I touch you as I do?” The next time you greet someone by shaking hands, or caress someone, let yourself become aware of what is happening as you touch that person. Then check out your observations with him or her: “just then, I felt. . .. How about you?”

Now we’re ready for another exercise. Again sit within touching distance of your partner and look at each other for one minute. Then take each other’s hands and close your eyes. Slowly explore the hands of your partner. Think about their form, their texture. Let yourself be aware of any attitudes you have about what you’re discovering in these hands. Experience how it feels to touch these hands and be touched by them. See how it feels to feel the pulses in your respective fingertips.

After about two minutes, open your eyes and continue touching at the same time you are looking. Let yourself experience what happens. Is there a change in your touching experience when you look?

After about thirty seconds, close your eyes, continue to touch, and experience any possible changes. After a minute, disengage your hands with a parting but not a rejection. Sit back and let yourself feel the impact of the whole experience. Open your eyes and share your inner space with your partner.

Try this variation: one person closes his or her eyes, and the second person uses hands to trace all the parts of the first one’s face, keeping awareness on the touch. Reverse this and then share your experience.

At this point in the experiment, many people say they become uncomfortable. Some say their sexual responses get stirred up, and it is like having intercourse in public. My response is, “It was your hands and faces you were touching, nothing else!” Some say they feel nothing; the whole thing seems stupid and silly. This saddens me as it could mean these people have constructed walls around themselves so they get no joy from physical contact. Does anyone ever really outgrow the wish and need for physical comforting and contact?

In the past ten years, people have begun to be more receptive about their touching needs. Hug passes and hug coupons have begun to appear in many places. Hugging is a nonsexual, very human way to get and give nurture. It is gradually spreading to men as well. Their skins get just as hungry as women’s skins. Maybe if people had more permission to gratify their needs for touching, they would not commit so much aggression.

I have noticed that when couples gradually begin to en-joy touching each other, their relationships improve in all areas. The taboo against touching and being touched goes a long way to explain the sterile, unsatisfying, monstrous experiences many people have in their sexual lives. This taboo also does much to explain to me why young people often get into premature sex. They feel the need for physical contact and think the only avenue open to them is intercourse.

As you went through these experiments, you probably realized that they are subject to individual interpretation. When our hands touch, you and I feel the touch differently. It is important for people to tell each other how the other’s touch feels. If I intend a loving touch and you experience it as harsh, I want to know that. Not knowing how we look or sound, or how our touch feels to someone else is very common, and since we often intend that which does not come across, we encounter unnecessary disappointment and pain in our relationships.

Now try smelling each other. This may sound a little vulgar. However, any of us who have used perfume knows that the sense of smell is important to how we are perceived. Many a potentially intimate relationship has been aborted or remained distant because of bad odors or scents. See what happens as you break your taboos against smelling, and let yourself tell and be told about your smells.

By this time, as you made contact with your eyes, ears, skins, and sharing one another’s inner space activities, you may already have a heightened appreciation of each other. It is equally possible that as you first looked, memories of old hurts were so strong that that was all you could see. I call this riding the garbage train. As long as you look now but see yesterday, the barriers will only get higher. If you encounter the garbage train, say so and dump it.

What is so important to remember is to look at one another in the present, in the here and now. Believe it or not,I have met hundreds of family pairs who have not touched each other except in rage or sex, and who have never looked at one another except in fantasy or out of the corners of their eyes. Eyes clouded with regret for the past, or fear for the future, limit vision and offer little chance for growth or change.

The next exercises are concerned with physical positions and how they affect communication.

Turn your chairs around back to back, about eighteen inches apart, and sit down. Talk to each other. Very quickly you will notice some changes. You become physically uncomfortable, your sense of enjoyment of the other decreases, and it’s hard to hear.

Add another dimension to the exercise: move your chairs about fifteen feet apart, remaining back to back. Notice the drastic changes in your communication. It is even possible to “lose” your partner entirely.

One of my first discoveries after beginning the study of families in operation was how much of their communication was carried on in precisely this way. The context is as follows: The husband is watching TV; the wife is behind the newspaper. Each pays attention elsewhere, yet they are talking about something important. “I hope you made the mortgage payment today,” says one. The other grunts. Two weeks later the eviction notice arrives. You can probably think of many similar examples of your own.

Don’t be fooled by thinking that to be polite requires great physical distance between people. I think having more than three feet between people puts a great strain on their relationship.

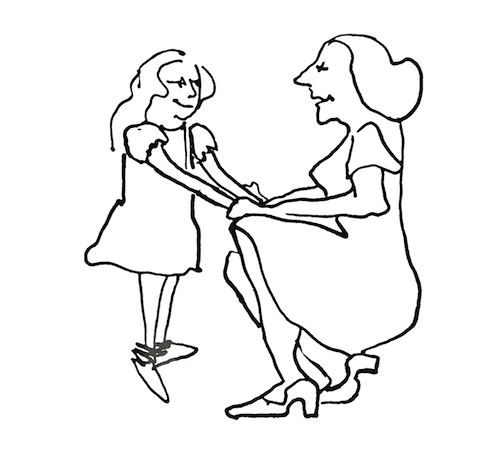

Now let’s try something else. Decide which of you will be A and which B. In the first round, A stands and B sits on the floor directly in front of A. Talk about how this feels. Stop after one minute. Share how it feels to talk in this position. Then change places and share again.

At one time we were all in the on-the-floor position in relation to the adults around us. It is the position of any young children in your family right now.

Still in these positions, let yourselves become aware of how your bodies feel. The sitter has to look up. Within thirty seconds, neck and shoulders will begin to ache, eyes and eye muscles will become strained, and the head will probably begin to ache. The stander will have to arch his or her back to look down, and back and neck muscles will begin to ache. It will probably become difficult to see as the strain grows.

(Give yourself just thirty seconds in these positions so you’ll know what I’m telling about. They become really horrible by sixty seconds.)

The physical discomfort engendered by these positions negatively influences the feeling tone of any interaction. This feeling tone is subliminal and therefore not conscious.

Everyone was born small and each of us spends ten to fifteen years (sometimes longer) being shorter than our partners. Considering the fact that most of our communication takes place in the positions described above, there is little wonder so many people feel so small all their lives. Understanding this, we can also understand why so many grow up with distorted views about themselves and their parents as people.

Try these same positions again, only this time using adult characters. Starting off with a male and female, for instance, visualize which of your parents was above and which was on the bottom.

Let’s look at this exercise from a slightly different perspective. Again, in the position of the last exercise, both of you look straight ahead and notice the scenery. From the floor you see knees and legs; and if you look down, you see feet and very big feet Look up and you see all the protrusions: genitals, bellies, breasts, chins, and noses. Everything is out of perspective.

So often I have heard reports from people about their parents’ mean looks, huge breasts, bellies, huge genitals, and chins, and so on. Then when I met the parents I often saw quite the opposite. The child had formed this menacing picture from an out-of-perspective position.

The parent sees the child out of perspective as well and might always envision the child as small. Images formed early in childhood can become the bases on which later experiences rest. These may never change.

Try this variation. Taking in the same up-and-down positions , malee hand contact. The one on the floor holds a hand and arm up; the one standing has an arm down. Thirty seconds is enough time for the upraised arm to get numb.

Inasmuch as the adult enjoys a more comfortable position , with the arm down, it might be difficult to realize the discomfort being inflicted on the child. The child might struggle to get away and the adult could become irritated at this “negative behavior.” All the poor kid wants is to get comfortable. The result is unintentional abuse.

How many times have you seen a child, both arms up, being virtually dragged along between parents? Or a hurrying parent dragging along his or her offspring by one arm on the bias?

Get into your standing and sitting positions for thirty seconds again. Then break eye contact and notice how quickly this change in positions relieves your neck, eyes, shoulders, and back.

Again, imagine how easy it would be for an adult to interpret this action on the part of a child as disrespectful. On the other hand, the child trying to contact her parent could interpret his glancing away as indifference or even rejection.

It would be natural for a child to tug at his parent for attention. This might annoy the parent to the extent that he or she slapped the pesky child. All of this would be humiliating , and the child could get hurt. This whole interaction is fertile breeding ground for engineering feelings of fear and hate in the child and rejection on the part of the adult. The sad part is that the causes are largely outside an individual’s awareness. If you have young children or children smaller than you in your home now, conduct a little research to learn how contact is now being made with them.

Suppose the parent responds to the tugging by delivering a supposedly reassuring pat on the child’s head but doesn’t gauge the force very well?

You, the stander, give the sitter a rather obvious pat on the head. Is it experienced as comforting or as a cranial explosion?

The significance of eye contact can be seen in this last set of exercises. For people to contact one another successfully, they need to be at eye level and facing one another. When images and expectations of one another are being formed, eye-level contact is essential between adults and children. First experiences have a great impact, and unless something happens to change them, those experiences will be the reference points for the future.

If you have young children, work it out so you contact them at eye level. Most of the time this means that adults will have to squat or, as an alternative, build eye-level furniture so the child can stand on his/ her own feet to be at eye level with you.

Now I would like to undertake some exercises that will help deepen understanding and make meaning between two people. Good human relations depend on people understanding one another’s meaning, whatever words they hap- pen to use. Since our brains work so much faster than our mouths, we often use a kind of shorthand, which might have an entirely different meaning for the other person than it does for us.

We learned from the picture-taking exercise that although we thought we were seeing, we were actually making up much of what we saw. This same kind of thing is possible with words. Let’s try this exercise.

Make what you believe to be a true statement to your partner. That person then repeats it to you verbatim, mimicking your voice, tone, inflection, facial expression, body position, movement. Check for accuracy, and if it fits, say so. If it doesn’t, produce your evidence. Be explicit; don’t make a guessing game out of this. Then reverse roles.

This exercise helps us focus on really listening to and really seeing another person. Listening and looking require one’s full attention. We pay a heavy price for not seeing and not hearing accurately: we end up by making assumptions and treating them as facts.

A person can look either with attention or without attention. Whoever is being looked at may not know the difference and assume he’s being seen when he is not. And what the first person thinks she sees is what she reports. If she happens to be in a position of power——as a parent, teacher, or administrator——she can cause him personal pain.

Let’s consider words a moment. When someone is talking to you, do those words make sense? Do you believe them? Are they strange, or do they sound like nonsense? Do you have feelings about the other person and yourself? Do you feel stupid because you don’t understand? Puzzled because you can’t make sense? If so, can you say so and ask questions? If you can’t, do you just guess? Do you not ask questions for fear you’ll be thought stupid, and thus you remain stupid? What about the feeling of having to be quiet?

These kinds of inner questions are natural and occasionally point to areas of specific concern. If you concentrate on these kinds of questions, you stop listening. I say it this way: “To the degree that you are involved with internal dialogue, you stop listening.”

As you try to hear the other person, you are, at the very least, in a three-ring circus. You are paying attention to the sound of the other person’s voice, experiencing past and future fears concerning you both, becoming aware of your own freedom to say what you are feeling, and finally concentrating on efforts to get the meaning from your partner’s words. This is the complicated inner space activity each person has, out of which communication develops and on which interaction between any two people depends.

Let’s go back to the exercises. Can you begin to feel how it is to use yourself fully to get the other person’s meaning? Do you know that words and meaning are not always the same? Do you know the difference between full listening and half listening? When you were imitating, did you find that your attention wandered and you made more errors in seeing?

My hope is that you can learn to engage yourself fully While listening. If you don’t want to or can’t listen, don’t pretend. just say, “I can’t be present right now.” You’ll make fewer mistakes that way. This is true of every interaction, but particularly true between adults and children. To listen freely requires the following:

The listener is giving full attention to the speaker and is fully present.

The listener puts aside any preconceived ideas of what the speaker is going to say.

The listener interprets what is going on descriptively and not judgmentally.

The listener is alert for any confusion and asks questions to get clarity.

The listener lets the speaker know that the speaker has been heard and also the content of what was communicated.

Now let’s go to the next part of the meaning exercises. Sit face to face with your partner, as before. Now one of you makes a statement you believe to be true. The other responds with, “Do you mean . . . " to indicate whether or not she or he has understood. The aim is to get three yeses. For example:

“I think it’s hot in here.”

“Do you mean that you’re uncomfortable?”

“Yes.”

“Do you mean that I should be hot, too?”

“No.”

“Do you mean that you want me to bring you a glass of

water?”

“No.”

“Do you mean that you want me to know that you are uncomfortable?”

“Yes.”

“Do you mean that you want me to do something about it?”

“Yes.”

At this Juncture at least the listener has understood the speaker's meaning. If the listener was not able to get any yeses, the speaker would simply have to explain what was meant.

Try this several times with the same statement, changing partners each time. Then try a question. Remember you are trying to get the meaning of the question, not to answer it. Do several rounds.

You are probably discovering how easy it is to misunderstand someone by making assumptions about what was meant. This can have serious results, as we've indicated, but they can also be funny.

I remember a young mother who was eager to clue into her son's sexual questions. Her opportunity came one day when he asked her, "Mommy, how did I get here?" Believe me, she made the most of her opportunity. When she finished, her son, looking extremely puzzled, said, "I meant, did we come by train or by airplane?" (The family had moved some months previously.)

As you were doing the meaning exercises, were you able to become fully aware of the trust and enjoyment that can come from engaging in a deliberate effort to understand? It is probably becoming more clear that everyone has different images for the same words. Learning about those images is called understanding.

Has the following ever happened at your house? You and your spouse meet at the end of the day. One of you says, “So, how was your day?” The other answers, “Oh, nothing special.”

What meanings are evident in this exchange? One woman who went through this fairly frequently said this was her husband’s way of turning her off. Her husband told me this was the way his wife showed him she didn’t care.

“So, how was your day?” can mean, “I had a tough day, and I’m glad you’re here. I hope it will go better now.”

It can mean, “You’re usually a grouch. Are you still grouchy?”

It can mean, “I am interested in what happens to you. I would like to hear about anything exciting that happened to you.”

“Oh, nothing special” can mean, “Are you really interested? I’d like that.”

It can mean, “What are you trying to trap me in now? I’ll watch my step.”

How about some examples from your family?

Many people assume everyone else already knows everything about them. This is a very common communication trap. Another is the hint method, in which people use one-word answers. Remember this old story? An inquiring reporter visited a rather plush old people’s home. As the director proudly escorted him around, the reporter heard someone call out “31” from a nearby room. Great laughter ensued. This procedure went on with several other numbers, all of which got the same response. Finally someone called out, “Number 11!” There was a dead silence. The reporter asked what was going on, and the director replied that these folks had been there so long they know all each other’s jokes. To save energy they had given each joke a number. “I understand that,” said the reporter. “But what about Number 11?” The director responded, “That poor guy never could tell a joke well.”

Another communication trap is the assumption that no matter what one actually says, everyone else should understand one. This is the mind-reading method.

I am reminded of a young man whose mother was accusing him of violating an agreement to tell her when he was going out. He insisted he had told her. As evidence he said, “You saw me ironing a shirt that day, and you know I never iron a shirt for myself unless I am going out.”

I think we’ve established that human communications involves mutual picture-taking, and that people may not share common pictures, the meanings they give the pictures, nor the feelings the pictures arouse. They then guess at each other’s meanings; the tragedy is that they may also treat these guesses as facts. To cope with this, develop the habit of immediately checking with the other person to determine whether your meanings match theirs.

Our guesses about one another are anything but 100 percent accurate. I believe this guessing procedure is responsible for a great deal of unnecessary estrangement between people. Part of the problem is that we are such sloppy talkers! We use words such as it, that, and this without clarifying them. This is particularly difficult for a child, who has fewer clues from experience. Any listener in this situation is in an impossible bind if the rules require that he act as though he understood.

Thousands of times I’ve heard one person say to another, “Stop that!” What is that? The second person may have no idea. Just because I see you doing something I want you to stop doing doesn’t mean you know what I’m talking about. Many harmful reactions can be avoided simply by remembering to describe what you are seeing and hearing——being specific about what you are saying.

This brings us to what I consider one of the most impossible hurdles in human relationships: the assumption that you always know what I mean. The premise appears as follows: If we love each other, we also can and should read each other’s minds.

The most frequent complaint I have heard people make about their family members is, “I don’t know how he feels.” Not knowing results in a feeling of being left out. This puts tremendous strain on any relationship, particularly a family one. People tell me they feel in a kind of no-man’s land as they try to make some kind of a bridge to a family member who doesn’t show or describe feelings.

Many people who are accused of this are often feeling very strongly, however. They may not realize they aren’t showing it. They believe themselves to be as transparent to others as they are to themselves. They reason, “She knows me. Therefore, she knows what I feel.”

I have a little experiment that I use to help people develop an awareness of this condition. I ask two people to discuss something,and I videotape their interchange. Then I play back the tape and ask these same two to respond to what they see in comparison to what they remember feeling as it happened. Many people are astonished because they see things of which they were not even in the remotest way aware when the tape was being made.

I remember a terrible ruckus in a family because the father sent his son to the lumber yard for a board. The child was obedient, wanted to please his dad, and thought he knew what was expected. He dutifully went and came back with a board that was three feet too short. His father, disappointed, became angry and accused his son of being stupid and inattentive.

The father knew how long a board he wanted, but it apparently had not occurred to him that his son wouldn’t know also. He had never thought of this and did not see it until we discussed it in the session. Then he was clear that he had not requested a specific length.

Here is another example. A sixteen-year-old son says at

5:30 P.M. on a Friday, “What are you doing tonight, Dad?”

Ted, his father, replies, “You can have it!”

Tom, the son, answers, “I don’t want it now.”

With irritation Ted snaps, “Why did you ask?”

Tom responds angrily, “What’s the use?”

What are they talking about? Tom wanted to find out if his father was planning to watch him play basketball that night. Tom didn’t ask his father directly because he was afraid Ted might say no; so he used the hint method.

Ted got the message that Tom was hinting, all right, but he thought it was a request for the family car. Tom thought his dad was putting him off. Ted then thought his son was ungrateful. These interactions ended with both father and son being angry and each feeling the other didn’t care. I believe these kinds of exchanges are all too frequent among people.

Sometimes people have become so used to saying certain things in certain situations that their responses become automatic. If a person feels bad and is asked how she feels, she will answer, “Fine,” because she’s told herself so many times in the past that she should feel fine. Besides, she probably concludes, no one is really interested anyway, so why not pick the expected answer? She has programmed herself to have only one string on her violin; and she has to use that one string with everything, whether or not it applies. The music is hardly enticing.

People can check out their mental pictures by depicting what they see or hear——by using descriptive, not judgmental language. Many people intend to describe, but they distort their pictures by including judgmental words. For example, my camera picture is that you have a dirt smudge on your face. IfI use descriptive words, I would say, “I see a dirt smudge on your face.” The judgmental approach (“Your face is a mess”) makes you feel defensive. With the descriptive statement, perhaps you feel only a little uncomfortable.

Two traps are implicit here: I read you in my terms and I hang a label on you. For example, you are a man, and I see tears in your eyes. Since I think men should never cry because that shows weakness, I conclude that you are weak, and I treat you accordingly. (Personally, I happen to feel just the opposite).

If I tell you what meaning I make of a given picture, avoid being judgmental, and tell you what I feel about it——and you do the same with me——at least we are straight with each other. We might not like the meaning we discover, but at least we understand.

I think you are ready now to try the ultimate risk with your partner. This time assign yourself the task of confronting your partner with three statements you believe to be true about him or her and three you believe to be true about yourself. You’ll probably be aware that these are your truths as of now; they may change in the future. To keep focused on telling your truths, try beginning with the following words: “At this time, I believe such and such to be true about you.” If you have a negative truth, see if you can put words to that. In my opinion, no relationship can be a nurturing one unless all states and aspects can be commented on openly and freely.

I used to tell my students they had it made when they could say straight to someone that he or she had a bad smell in such a way that the information was received as a gift. It is painful at the outset but definitely useful in the long run. Many people have reported to me that, contrary to their expectations, relationships stood on firmer, more nurturing and trusting ground when they found they could be straight with negative as well as positive content. Remember, one does not have to approach something negative, negatively. One can do it positively. Maybe the chief difference is being descriptive.

On the other hand, many people never put words to their appreciation. They just assume the others know of it. When one voices objections only, without acknowledging satisfaction as well, estrangement and resentment arise.

Who doesn’t like (and need!) a pat on the back from time to time? This “pat” could be as simple as the statement, “I appreciate you.”

I recommend that families do the educational exercise I just described at least once a week. After all, the first and basic learning about communication comes in the family. Sharing your inner space activity with one another accomplishes two important things: becoming really acquainted with the other person and thus changing strangeness to something familiar, and also making it possible to use your communication to develop nurturing relationships——something we all continue to need.

You could now be more aware that every time two people are together, each has an experience that affects him or her in some way. The experience can serve to reinforce what was expected, either positively or negatively. It may create doubts about the other’s worth and thus create distrust; or it may deepen and strengthen the worth of each, and the trust and closeness between them. Every interaction between two people has a powerful impact on the respective worth of each and what happens between them. This includes the tasks they share in common, such as child rearing.

If encounters between a couple become doubt-producing, the individuals involved begin to feel bad about themselves against each other. They begin to look elsewhere——to work, to children, to other sexual partners——for their nurturing. If a husband and wife begin to have sterile and lifeless encounters, they eventually become bored with one another. Boredom leads to indifference, which is probably one of the worst human feelings and, incidentally, one of the real causes of divorce. I am convinced that anything exciting, even dangerous, is preferable to boredom. Fighting is better that being bored. You might get killed from it, but at least you feel alive while it goes on.

When communication between any pair or in any group produces something new and interesting, then aliveness and/ or new life comes into being. A deepening, fulfilling relationship develops, and each person feels better about him- or herself and the other.

I hope that now, after the many exercises you have experienced, my earlier words about the communication process will have more meaning: Communication is the greatest single factor affecting a person’s health and relationship to others.