20. Adolescence

The teenager’s job is a huge one. Moved by the energy released through puberty, the psychological necessity for becoming independent, and social expectations for becoming successful, the adolescent has tremendous pressure while finding a way around a new world. Put this together with the fact that there are no marked paths to follow, and you have the wonder and the scariness that adolescence produces.

We need to recognize this condition. It is tricky for both the adolescent and the parents. Adults need to create a context in which this growth can take place, in much the same careful way we made the house safe for the children when they were toddlers. We need to do it in a way that preserves the adolescents’ dignity, develops their sense of self-worth, and gives them useful guidelines, all of which will help them become more socially mature.

An adolescent’s psychological context needs to be able to accommodate mood swings, seemingly irrational ideas, occasional bizarre behavior, new vocabulary, and awkward performances. Each or all of these arise as adolescents play with their power, their autonomy, and their dependence and independence.

To successfully negotiate the adventure of adolescence, both parents and teenagers need positive images. Teens have made some great accomplishments requiring great risks. Yours may be among them. Make a scrapbook with pictures and stories about adolescents who used their energy for wonderful purposes: starting backyard businesses, organizing visits to elders, or overcoming obstacles to achieve a goal. This will help to dissolve some of your fear. Enlist the help of your teenager to find these stories. Celebrate the risks teens take that pay off.

I have heard parents complain about their teenagers, “They never sit still. They always have to be doing something.” This is par for the course. Wise parents accept this restlessness and find graceful ways to live while temporary storms rage. They carefully choreograph new contexts that nurture the buds which can then become blossoms. The result is the bearing of good fruit.

Negotiating the adolescent stage is neither quick nor easy. Both parents and adolescents need to develop patience, and keep talking and loving, to make it work. In this period of tremendous change, everyone becomes new to each other, and people have to get to know one another all over again. Approaching this with more love than fear will often be the difference between success and failure.

I have often said to parents, “If it isn’t illegal, immoral, or fattening, give it your blessing.” We do much better with helping people if we find and support all the places we can appropriately say yes, and say only the no’s that really matter.

Every adult who is reading this book has survived adolescence——some with scars. some with still-open wounds, and all with texture. The differences between texturing and scarring can be explained as follows. Texturing comes from using oneself to accumulate wisdom through learning to deal with one’s frustration and conflicts, become responsible, and meeting other of life’s realities. Scarring comes as the result of a broken spirit. The open wound shows there has been no healing; not even the thin skin has grown over. This results in seriously handicapped psychological and social conditions. My experience is that parents will do all they can to avoid leaving open wounds with their adolescents. Sometimes the parents’ wounds are still open too, and it is hard for them to deal well with their teenagers.

One approach is for parents to form their own groups for support, brainstorming, and practicing congruent communication. This may be especially useful for families in which both parents are away during the day and so need to find other people and resources in the community for support.

Parents often meet this period with negative fantasies stemming from memories of their own adolescence as well as from horror stories about teenage abuses of alcohol, drugs, sex, and violence. The problems of sex and violence seem forbidding, but we need to remember that teenagers are more like adults than they are different. If I pinch an adult hard enough, he or she will hurt just like any adolescent. Much experimenting with sex comes out of a hunger for touch, the need to be held and stroked. And much teen violence comes out of a desperate desire not to appear weak or needy, just as it does with adults.

Addicted teenagers represent a growing percentage of our total adolescent population. These behaviors are so dramatic that it may feel like many more persons are involved than really are. Aside from percentages and statistics, though, many parents have cause for concern about their particular child. Parents who ignore the signs of possible addiction to alcohol and drugs are perpetuating the problem by the same avoidance that is characteristic of people who behave in these ways.

Excellent help exists in programs all over the world as outgrowths of Alcoholics Anonymous, Alateen, Alanon, and Adult Children of Alcoholics are groups that can help and are listed in the telephone directories under Alcoholics Anonymous. In many communities, hotlines also exist to handle calls about parental stress, sexual health, sexual abuse, domestic violence, suicide prevention, and other crises. If you do not find the number in your directory or with the help of a Directory Assistance operator, your community’s Mental Health department may be able to refer you to the resources available in your area.

Dealing with serious problems and minor problems both involve finding positive images. Once we can see our way out of a situation, we’re halfway there. The same holds true for general feelings of anxiety about adolescence. Look around and you will see scores of fine things going on with teenagers. One of these teens could be yours. Have you taken the time to tell your adolescent what you like about what he or she is doing? If not, do it now! Do it every time you notice positive actions. And do it when your teenager shows greater awareness or makes positive choices while trying to resolve a mistake, as well.

When parents and adults take a balanced attitude toward what is a wonderful, exciting, and sometimes a frightening journey, they increase their prospects of being successful guides to their adolescents. We are a different kettle of fish in this period than in any other stage of development, so both parents and teens start out in the dark.

As mentioned, one very big change during puberty is the awakening of a level of energy previously unknown to that individual. This energy is scary and calls for safe, appropriate, and fulfilling ways to have healthy expression. Sports, exercise, and stimulating mental and physical work are effective and nourishing ways to express it. Organized programs and working for causes are two other ways. Adolescents are often idealistic and will work hard to achieve their goals. Help them find a context where this can happen. Programs such as Outward Bound, for example, help people to navigate through the tough parts of their adolescence. This program takes place in the wilderness, creating opportunities for young people to meet their fears, develop their courage, and learn teamwork. While this particular program was developed to help adolescents who were having a rough time, it is good for any teenager. For that matter, similar programs now exist for adults, who can also benefit from these learnings.

Meeting the challenge of harnessing energy and directing it successfully is one aim of adolescence. The picture of excited, energetic race horses pacing nervously at their stalls

as they are forced to wait for the starting gate to open is an apt analogy for the average teenager. They are spirited and want to win the race. I think adults, without meaning to, contribute to teenage difficulties by not providing adequate purposeful activities. Adolescents are not monsters. They are just people trying to learn how to make it among the adults in the world, who are probably not so sure themselves.

I think it is this energy that frightens adults the most. To handle their fears, parents often inundate their teenagers with “don’ts” and other forms of control. just the opposite is necessary. Adolescents need to be encouraged to create adequate channels to direct their newfound energy. They also need clear boundaries. They need love and acceptance. The important skill to learn is to accept the person’s value while at the same time helping to modify his or her behavior.

For example, rather than tossing off admonishments such as “Now, be careful. Remember you’re a good girl” to a daughter going out on a date, parents can help by teaching her how to set her own priorities, in advance of the situation. A young person who has carefully thought out his or her attitudes can respond to pressure by saying, “Thanks for asking me, but what you ask at this point doesn’t fit for me, so the answer is no.”

When I have been privy to parent-adolescent collisions, the most successful way I have found to be helpful is to establish a positive relationship between them based on each person’s humanness and caring. It is largely futile to attempt change through control or threat. When each person can be regarded as an individual of worth, real changes can take place and do. I would like parents to see themselves becoming a laboratory of resources for their children.

Adolescents are neither stupid nor perverse; nor are parents. Both only seem like that in the eyes of the other when they can’t make contact, when they present each other with implied threats of estrangement, and when they trigger catastrophic expectations.

To develop a foundation for change, I suggest the following steps:

You, the parent, need to spell out your fears so your teenager can hear them.

You, the adolescent, need to be able to say what is happening with you and be believed. You need to be able to tell your fears and know you will be heard without criticism or ridicule.

You, the parent, need to show willingness to listen and to show that you understand. Understanding does not equal excusing. It simply provides a clear basis from which to go forward.

You, the adolescent, can make it clear that you need your parent to listen, not to give advice unless you ask for it.

You, the parent, need to understand that your teenager may not act on the advice you give.

Now a meaningful dialogue can take place between people who feel equal in value and therefore can develop new, constructive behavior. A stronger relationship can also develop as a result.

Many adults have not mastered the skill and art of being congruent, so even when they want to be congruent, they seem to be controlling (see Chapter 2 on self-esteem). I have never seen parents lose credibility in their teenager’s eyes when they admit honestly what they don’t know or when they indicate they identify with some pain or negative feeling their teenager may have (“I was scared, too . . .” or “I know what it feels like to lie,” etc.).

Through conducting hundreds of repair processes between parents and teenagers, I learned most parents have not completed their own adolescence. They really don’t feel like the wise leaders they are supposed to be. Under these circumstances, it is hard for them to help their adolescents learn what they have not themselves yet learned. They have my compassion. Many adults try to handle this by faking. That is, they try to act like they know when they don’t. That works sometimes but is ill advised as a blanket technique. Teenagers almost always know what is going on.

I encourage parents to take credit for their inadequacies and limitations, making their acknowledgment into a badge of honesty and therefore high self-worth. The parent and child can then become a team and work together in the interests of both.

One instance that I remember concerned a teenager who was not attending school. Both parents had pleaded and threatened, all to no avail. I learned that neither of these parents had completed their education, and they vowed their son would complete his. They wanted to give to him what they had not received. It was a love act on their part toward their son; but because of the way it was presented, he interpreted it as control. When I facilitated a trust between the parents and their son, all were able to hear each other. It turned out that everyone agreed on the goal. Once he understood his parents’ fears, the son was able to trust them and to invest his energy in going back to school because he wanted to, and not because he felt compelled to.

The troublemaker in this scenario was not the goal of education, but the prevailing win-lose attitude. This is inherent in the power messages of“I will tell you what to do and you will do it,” “It is good for you, you have to,” and so on. Predictably, the teenager answered, “You can’t tell me what to do”; “I won’t do it”; and “I don’t care about education.” Many parents and children get into this fix. I call it cutting off your nose to spite your face. The words were about school; the counter- or meta-message was about power and control (“Who has the right to tell who what to do?”). The parents intended to be helpful, yet their effect was to create a war (see chapter on Communication).

I find this particular behavior is the biggest troublemaker between parents and teenagers. In fact, when a conflict over power and control exists between any two people, regardless of age, rank, or sex, trouble will brew. It manifests itself in the familiar communication stances I described earlier: blaming, placating, being super-reasonable or computing, and being irrelevant.

This win-lose attitude makes up the power struggle. The underlying issue in every power struggle is who will win; and people usually assume that only one will. I believe that it is a personal tragedy if either loses: their relationship suffers, and their self-esteem drops. Parents and teenagers need each other, and they can learn to use win-win attitudes. For example, the young person says, “It’s only Wednesday, and I’m out of money. I need some more.” The parent who practices win-lose will say, “Too bad. I have no more, so you don’t get any.” In a win-win approach, the parent says, “That’s happened to me, too, and it doesn’t feel very good. I won’t have any money until payday, but let’s see how we can get what you want, and maybe we can learn how to budget your money better.”

In the first way (controlling), the parent is trying to teach by punishment. In win-win, the parent teaches negotiation and creativity, and reinforces caring. Money was not a solution in either mode.

Teenagers have a right to expect their parents to be leaders in the growth process, and honesty is extremely important in such dealings. It is actually the only basis for trust. Teenagers will not be honest with adults who are not honest with them. In this case, it is emotional honesty that counts most.

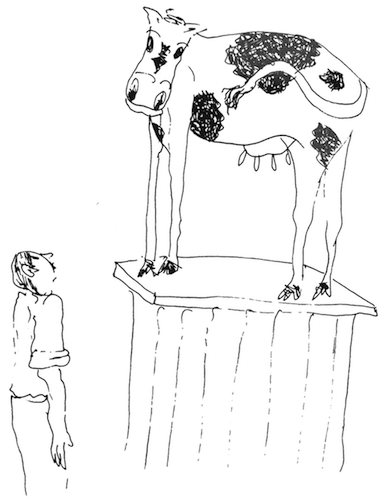

A big part of the adolescent period is to find out what the world is all about. Adolescents become philosophical, questioning everything under the sun. I think this is good. Adults can benefit by the scrutiny that adolescents give our sacred cows and their eagerness to try out lots of things.

Adults need to support this discovery process so that everyone enjoys maximum outcomes with minimum disruptive risk. Families with people in the adolescent stage can thus refresh their lives if they choose to. A lot of adults have become jaded about hope and about their conclusions. Their adolescents' quests and questions give them a chance to review and renew.

Adults need to be clear about their boundaries and bottom lines and act in accordance with them. Each needs to know where she or he stands with the other. This is what respect is all about. Each of us has limits.

For example, if you, the parent, figure out from your best reality that you can spare your car once a week for your teenager to use, stick to that. If you give the car out on a whimsical basis ("You can have it sometimes") or on a punitive basis ("You didn't do such and such, so you can't have it"), you are likely to run into trouble. Be honest and real about your own boundaries.

One goal for adults that gains respect from the teenager is keeping agreements. Don’t give a promise unless you mean it. If you sacrifice your boundaries so your child will love you, the chances are the child will mistrust you and you will resent the child. Everyone loses.

Have you noticed that parents and teenagers rarely enjoy the same activities? Teenagers want to go off in different directions and often with their peers. This is quite normal. It does not mean that the teenager is deserting or rejecting the family. Peers often assume a stronger role than parents during this time. Parents need to find genuine ways to receive their adolescents’ friends. Parents also need to recognize that adolescents are dissolving their basic dependence on parents and are preparing for the adult stage. Instead, parents have to give up being control figures in their child’s life. Parents need to become helpful guides. In this spirit, parents and adolescents can continue to have in common their humanness and mutual respect.

Remember that when one is an adolescent, one feels forty years old one minute, and five the next. This is, of course, how it needs to be. When adults say critically to adolescents, “Act your age,” they forget the confusion teenagers experience in this stage. When adolescents know they are loved, valued, and accepted unconditionally, they can accept responsible adult leadership more easily. They desperately need to have adults who care for them who can and will discreetly plan this journey with them.

Instead of surrounding the adolescent with a lot of restraints and restrictions, concentrate instead on developing a relationship based on honesty, humor, and realistic guidelines. More than anything else, adolescents need sensitive, flexible relationships with trusted adults. If they have this, they can weather the storms that are sure to rise from time to time through this exciting, scary, turbulent period. At the end awaits a wonderful jewel: a newly evolved person. Give your blessings to the good relationships your adolescents have with other mature adults. Teens may need explicit permission to do this (so that they do not feel disloyal).

Give all you can when you have your adolescent’s listening car, which you will have when you are trusted. When you don’t have that attention, don’t demand it. It won’t work anyway and will only build walls if you insist. Wait until the ambience is better. You may remember how little enthusiasm you had for the adults who insisted that you follow their advice, instead of helping you to discover what you needed to learn.

Above all, adolescents are striving to accomplish their autonomy and identity. They endure many false starts, unrewarding paths, and, often, hormonal storms. These are natural steps in development. In hormonal storms, teens experience intense feelings. It’s important that parents refrain from discounting these strong emotions. (“It’s only puppy love,” for example, or “Yeah, yeah, everybody goes through this. C’mon, snap out of it and get on with your life!”).

I once heard a famous sculptor say that he waits to see what the stone will bring forth instead of imposing his ideas on it. Parenting adolescents is even more like that.

I want to switch now to the teenager’s perspective. “What I need most is to feel loved and valued, no matter how foolish I may seem. I need someone who believes in me because I do not always believe in myself. Frankly, I often feel terrible about myself. I feel I am not strong enough, bright enough, handsome or pretty enough, for anyone to really care about me. Sometimes I feel I know everything and I can stand against the world. I feel intensely about everything.

“I need someone who will listen to me uncritically for what helps me to center myself. When I have a defeat, lose a friend or a game, I feel like the world has collapsed. I need a loving hand to comfort me. I need a place to cry where no one will make fun of me. On the contrary, I need someone

who will just be with me. I also need someone to say ‘stop’ to me clearly. But please don't give me a lecture and remind me of all my past goofs. I already know them and feel guilty about them.

“Above all, I need you to be honest with me about me and about you. Then I can trust you. I want you to know I love you. Please don't have your feelings hurt when I love others. That won’t take‘ away from you. Please keep on loving me.”

When we love people, we tend to want to make them perfect, in our eyes. This often results in meddling, which no one——adult or adolescent——likes. Using the congruent forms of communication you’ve learned in this book, you know you can stop meddling. You need to learn to recognize meddling when you are doing it.

You will know that the journey of an adolescent has been successfully completed when he or she shows to handle dependence, independence, and interdependence; has a high sense of self-worth; and knows how to be congruent. These new attributes will probably include a transformed relationship to you, the parents. It will reflect a willingness to work together as a team.

I suggest that at the end of the adolescent stage, the guides (usually the parents) give a party. Its purpose will be to clearly validate the new place between parents and child. The person is no longer adolescent; he or she is adult. This ritual celebration brings parents and child together as peers in the world.

I feel that adolescence has served its purpose when a

person arrives at adulthood with a strong sense of self-esteem, the ability to relate intimately, to communicate congruently, to take responsibility, and to take risks. The end of adolescence is the beginning of adulthood. What hasn’t been finished then will have to be finished later. I am counting on more enlightened guidance through adolescence by parents and other adults to bring forth young adults who will be capable of being better people and making this world a safer, more exciting, and more human place to live.