9. The Rules You Live By

Webster states that a rule is an established guide or regulation for action, conduct, method, or arrangement. In this chapter I intend to move away from this flat definition and show you that rules are actually a vital, dynamic, and extremely influential force in your family life. Helping you as individuals and as families to discover the rules by which you live is my goal. I think you’re going to be very surprised to discover that you may be living by rules of which you’re not even aware.

Rules have to do with the concept of should and should not. They form a kind of shorthand, which becomes important as soon as two or more people live together. The questions of who makes the rules, from what material are they made, what they do, and what happens when they are broken will be our concerns in this chapter.

When I talk with families about rules, the first ones they mention usually concern handling money, getting the chores done, planning for individual needs, and dealing with infractions. Rules exist for all the other contributing factors that make it possible for people to live together in the same house and grow or not grow.

To find out about the rules in your family, sit down with all family members present and ask yourselves, “What are our current rules?” Choose a time when you all will have two hours or so. Sit around a table or on the floor. Elect a secretary who will write the rules down on a piece of paper to help you keep track of them. Don’t enter into any arguments at this point about whether the rules are right. Nor is this the time to find out whether they are being obeyed. You’re not trying to catch anybody. This exercise takes place in the spirit of discovery, much in the manner of poking about in an old attic just to find out what’s there.

Maybe you have a ten-year—old boy who thinks the rule is that he has to wash the dishes only when his eleven-year- old sister is justifiably occupied somewhere else. He figures he is a kind of backup dishwasher. His sister thinks the rule is that her brother washes the dishes when his father tells him to. Can you see the misunderstanding that can result? This may sound foolish, but don’t kid yourself, it could be happening in your home.

For many families, simply sitting down and discovering their rules is something very new, and it often proves enlightening. This exercise can open some exciting new possibilities for more positive ways of living together. I’ve found that most people assume that everyone else knows what they know. Irate parents tell me, “She knows what the rules are!” When I pursue the matter, I often find this isn’t the case. Assuming that people know the rules is not always warranted. Talking over your rule inventory with your family can clear the way to finding reasons for misunderstanding and behavior problems.

For example, how well are your rules understood? Were they fully spelled out, or did you think your family could read the rules in your mind? It is wise to determine the degree of understanding about rules before deciding somebody has disobeyed them. Perhaps as you look at your rules now, you may find that some of your rules are unfair or inappropriate.

After you have written down all the rules your family thinks exist and cleared up any misunderstanding about them, go on to this next phase. Try to discover which of your rules are still up to date and which are not. As fast as the world changes, it is easy to have out-of-date rules. Are you driving a modern car with Model T rules? Many families are doing just this. If you find that you are, can you bring your rules up to date and throw away the old ones? One characteristic of a nurturing family is the ability to keep its rules up to date.

Now ask yourself if your rules are helping or obstructing. What do you want them to accomplish? Good rules facilitate instead of limiting.

All right. We’ve seen that rules can be out of date, unfair, unclear, or inappropriate. What have you worked out for making changes in your rules? Who is allowed to ask for changes? Our legal system provides for appeals. Do the members of your family have a way to appeal?

Go a little farther in this family exploration. How are rules made in your family? Does just one of you make them? Is it the person who is the oldest, the nicest, the most handicapped, the most powerful? Do you get the rules from books? Neighbors? From the families in which the parents grew up? Where do your rule come from?

So far the rules we’ve been discussing are fairly obvious and easy to find. There is another set of rules, however, which is often submerged and much more difficult to get one’s fingers on. These rules make up a powerful, invisible force that moves through the lives of all members of families.

I’m talking about the unwritten rules that govern the freedom to comment of various family members. What can you say in your family about what you feel, think, see, hear, smell, touch, and taste? Can you comment only on what should be rather than what is?

Four major areas are involved with this freedom to comment.

What can you say about what you’re seeing and hearing?

You have just seen two other family members quarrel bitterly. Can you express your fear, helplessness, anger, need for comfort, loneliness, tenderness, and aggression?

To whom can you say it?

You are a child who has just heard Father swear. There is a family rule against swearing. Can you tell him?

How do you go about it if you disagree or disapprove of someone or something?

If your fifteen-year-old daughter or son reeks of marijuana, can you say so?

How do you question when you don't understand (or do you question)?

Do you feel free to ask for clarification if a family member is not clear?

Living in a family provides all kinds of seeing and hearing experiences. Some of these bring to the heart. some bring pain, and perhaps some bring a feeling of shame. If family members cannot recognize and comment on whatever feelings are aroused, the feelings can go underground and gnaw away at the roots of the family's well-being.

Let’s think about this for a moment. Are there some subjects that must never be raised in your family? The kinds of things I am referring to include: your oldest son was born without an arm, your grandfather is in jail, your father has a tic, your mother and father fight, or either parent was previously married.

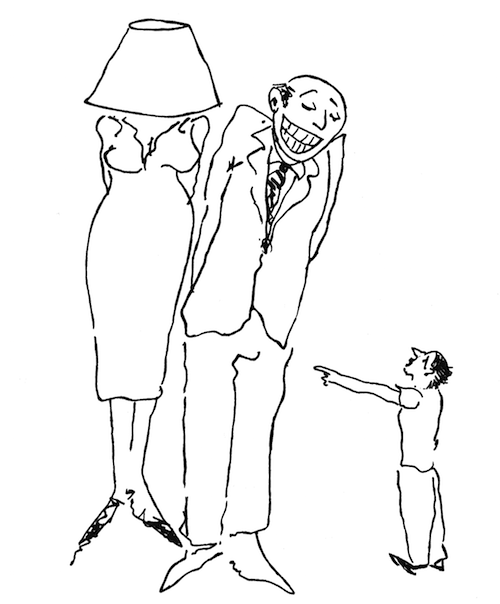

Perhaps the man in your family is shorter than the average man. The rule honored by all members of the family is that no one talks about his shortness: no one talks about the fact that they can’t talk about his shortness, either.

How can you expect to behave as though these family facts simply don’t exist? Family barriers against talking about what is or what has been provide a good breeding ground for troubles.

Let’s consider another angle to this perplexing situation. The family rule is that one can talk about only the good, the right, the appropriate, and the relevant. When this is the case, large parts of present reality can’t be commented on. In my opinion, there are no adults and few children living in the family or anywhere else who are consistently good, appropriate, and relevant. What can they do when the rules say no one can comment on these kinds of things? As a result some children lie: some develop hatred for, and estrangement from, their parents. Worst of all, they develop low self-worth, which expresses itself as helplessness, hostility, stupidity, and loneliness.

The simple fact is that whatever a person sees or hears has an impact on that person. He or she automatically tries to make an internal explanation about it. As we’ve seen, if there is no opportunity to check out the explanation, then that explanation becomes the “fact.” The “fact” may be accurate or inaccurate, but the individual will base her or his actions and opinions on it.

Forbidden to comment or question, many children grow up to be adults who see themselves as versions of saints or devils instead of living, breathing human beings who feel.

All too often, family rules permit expressing feeling only if it is justified, not because it is. Thus, you hear expressions like “You shouldn’t feel that way” or “How could you feel like that? I never would.” The point here is to make a distinction between acting on your feelings and telling your feelings: to talk about feeling suicidal is not the same as killing yourself. This distinction makes it easier to give up the rule “Thou shalt have only justified feelings.”

If your rules say that whatever feeling you have is human and therefore acceptable, your self can grow. This is not saying that all actions are acceptable. If the feeling is welcome, you have a good chance to develop different courses of action——and more appropriate action at that.

From birth to death, human beings continually experience a wide range of feelings——fear, pain, helplessness, anger, joy, jealousy, and love——not because they are right, but because they are. Giving yourself permission to get in touch with all parts of your family life could dramatically change things for the better. I believe that anything that exists can be talked about and understood in human terms.

Let’s get into some real specifics. Take anger. Many people are not aware that anger is a necessary human emergency emotion. Because anger sometimes erupts into destructive actions, some people think anger itself is destructive. It isn’t the anger, but the action taken as a result of the anger that can be destructive.

Let’s consider an extreme example. Suppose I spit at you. For you that could be an emergency. You might feel you have been attacked and feel bad about yourself and angry at me. You might think of yourself as unlovable (why else would I have attacked you?) You feel hurt, low-pot, lonely, and perhaps unloved. Although you act angry, you are feeling hurt——of which you are only remotely aware. How would you show what you are feeling? What would you say? What would you do?

You have choices. You can spit back. You can hit me. You can cry and beg me not to do it again. You can thank me. You can run away. You can express yourself honestly and tell me how angry you feel. Then you’ll probably be able to be in touch with your hurt, which you can tell me. Then you can ask me how I happened to spit at you.

Your rules will guide you in how to express your responses. If your rules permit questions, you can ask me and then understand. If your rules don’t permit questions, you can guess, and maybe make a wrong guess. The spitting could represent many things. You could ask yourself, did she spit because she doesn’t like me? Because she was angry with me? Because she is frustrated with herself? Because she has poor muscle control? Did she spit because she wanted me to notice her? These possibilities may seem farfetched, but think about them awhile. They aren’t really so farfetched at all.

Let’s talk about anger some more because it’s important. It’s not a vice; it is a respectable human emotion that can be used in an emergency. Human beings can’t live out their lives without encountering some emergencies, and we all will find ourselves in a state of anger at times.

If an individual wants to qualify as being a Good Person (and who doesn’t?) she or he will try to hold in occasional feelings of anger. Nobody is fooled, though. Have you ever seen anyone who’s obviously angry but trying to talk as if he or she were not? Muscles tighten, lips go tight, breathing gets choppy, skin color changes, eyelids tighten; sometimes the person will even puff up.

As time goes on, the person whose rule says anger is bad or dangerous begins to tighten up further inside. Muscles, digestive system, heart tissue, and artery and vein walls get tight, even though the outside looks calm, cool, and collected. Only an occasional steely look in the eye or a twitchy left foot will indicate what the person is really feeling. Soon all the physical manifestations of sickness that come from tight insides, such as constipation and high blood pressure, show up. After a while the person is no longer aware of the anger as such but only of the pain inside. He or she can then truthfully say, “I don’t get angry. Only my gall bladder is acting up.” This person’s feelings have gone underground; they are still operating, but out of the range of awareness.

Some people don’t go this far but instead develop a storage tank for anger. It fills up and explodes periodically at small things.

Many children are taught that fighting is bad, that it is bad to hurt other people. Anger causes fighting, therefore anger is bad. The philosophy with far too many of us is, “To make a child good, banish the anger.” It is almost impossible to gauge how much this kind of teaching can harm a child.

If you permit yourself to believe that anger is a natural human emotion in specific situations, then you can respect and honor it, admit it freely as a part of yourself, and learn the many ways of using it. If you face your angry feelings and communicate them clearly and honestly to the person involved, you will drain off much of the “steam” and the need to act destructively. You are the chooser and, as such, can feel a sense of managing yourself. As a result, you can feel satisfied with yourself. Family rules about anger are basic to whether or not you grow with your anger or allow yourself to die from it, a little at a time.

Now let’s consider another really important area in family life: affection among family members, how it is expressed, and the rules about affection.

I have found all too often that members of families cheat themselves in their affectional lives. Because they don’t know how to make affections safe, they develop rules against all affection. This is the kind of thing I mean: fathers often feel that after their daughters reach the age of five, they are no longer supposed to cuddle them as it may be sexually stimulating. The same holds true, although to a lesser degree, with mothers and their sons. Too, many fathers refuse to show overt affection to their sons because affection between males might be taken as homosexual.

We need to rethink our definition about affection, whatever sexes, ages, or relationships are involved. The main problem lies in the confusion many people experience between physical affection and sex. If we don’t distinguish between the feeling and the action, then we have to inhibit the feeling. Let me put it bluntly. If you want problems in your family, play down affection and have lots of taboos about discussing or having sex.

Displays of affection can have many meanings. I’ve been hugged in such a way that I wanted to slug the hugger. Other times a hug is an invitation to sexual intercourse; an indication of simply being noticed and liked; or an expression of tenderness, a seeking to give comfort.

I wonder how much of the truly satisfying, nurturing potential of affection among family members is not enjoyed because family rules about affection get mixed up with taboos about sex.

Let's talk about that. If you had seen as much pain as I have that clearly resulted from inhuman and repressive attitudes about sex, you would turn yourselves inside out immediately to attain an attitude of open acceptance, pride, enjoyment, and appreciation of the spirituality of sex. Instead, I have found that most families employ the rule, "Don't enjoy sex——yours or anyone else's——in any form." The common beginning for this rule is the denial of the genitals except as necessary nasty objects. “Keep them clean and out of sight and touch. Use them only when necessary and sparingly at that.”

Without exception, every person I have seen with problems in sexual gratification in marriage, or who was arrested for any sexual crime, grew up with these kinds of ta- boos against sex. I’ll go further. Everyone I have seen with any kind of coping problem or emotional illness also grew up with taboos about sex. These taboos apply to nudity, masturbation, sexual intercourse, pregnancy, birth, menstruation, erection, prostitution, all forms of sexual practice, erotic art, and pornography.

Our sex, our genitals, are integral parts of ourselves. Unless we openly acknowledge, understand, value, and enjoy our sexual side, we are literally paving the way for serious personal pain.

I once headed up a program for family life education in a high school of about eight hundred students. Part of the program concerned itself with sex education. I had a box into which young people could put questions they felt they couldn’t ask openly. The box was usually full. I would then discuss these questions during the class period. Nearly all the students explained that they would not have been able to ask their parents these questions for at least three common reasons: their parents would become angry and accuse them of bad conduct; parents would feel humiliated and embarrassed and would probably lie; or they simply wouldn’t know the answers. So the students were sparing themselves and their parents, but at the cost of remaining ignorant and seeking information somewhere else. These young people expressed gratitude for the course, and for my accepting, knowledgeable, and loving attitude; they also were feeling better about themselves. I remember two questions particularly: an eighteen-year-old asked, “What does it mean if I have lumps in my semen?” and a fifteen-year-old boy asked, “How can I tell if my mother is in the menopause? She seems awfully irritable now. If she is, then I can understand and will treat her nicely; otherwise I’m going to tell her how mean she is. Should I tell my father?”

How would you, as parents, feel about being asked these questions? If asked, what would you say?

In quite a nice follow-up to this course, the students asked if I’d run a similar course for their parents. I agreed. About a quarter of the parents came to it. I had the same box, and I got very similar questions.

In short, I think we can forgive ourselves for not always knowing the complexities of our sexual selves. But it is psychologically dangerous to go on in ignorance and cover up by a don’t-talk-about-it attitude, implying that sexual knowledge is bad, criminal. Society and the individuals who make it up pay heavily for this kind of ignorance.

Fear on the part of family members has much to do with taboos and rules about secrets, even though adults may express the rules as “protection for the kids.” This is like another taboo I find rampant in families: the adult mystique. Almost wholly invented by adults to “protect the children,” this rule is usually expressed as, “You are too young to . . . ” The implication is that the adult world is too complicated, too terrifying, too big, too evil, too pleasureful for you, the mere child, to discover. The child gets to feeling there must be some magic password and that when he or she comes of age, the doors will automatically open. I find adults in droves who haven’t discovered the password.

At the same time, the “you-are-too-young-to” pattern implies that the child’s world is inferior. “You are just a child; what do you know?” adults say, or, “That is childish.” Since gaps obviously exist between what an individual child is ready to do and might like to do, I think the best preparation is to teach children how to make bridges for these gaps, rather than denying them the opportunity of bridging the gaps.

Another aspect of this business of family taboos concerns secrets. Common examples of family secrets are: that a child was conceived before the parents were married, that a mate conceived a child who was later adopted, or that a mate is hospitalized or jailed. These kinds of secrets are usually heavily shrouded in shame.

Some of the biggest secrets involve parents’ behavior during their adolescent years——the rule being that, by definition, no parents ever did anything wrong; it is only “you kids” who ever misbehave. This kind of thing has happened so many times that if I hear a parent getting hysterical about something her or his child is doing, I look immediately to see whether the child’s behavior has stirred up a secret in the parent’s youth. The behavior of the child may not duplicate that of the parent, but it can come close. My job in this in- stance is to help the parent get rid of old shame so he or she doesn’t have to lock a secret part away. Then the parent can deal rationally with the child.

Present secrets are also shrouded in shame. Many parents try to hide their goings-on from their children (“to protect them”). Examples of such present secrets that I have run across are that the father or mother (or both) has a lover, either or both drink, or they don’t sleep together. Again, people tell themselves that if it isn’t talked about, it doesn’t exist. This simply does not work, ever, unless everyone you are “protecting” is mute, deaf, and blind.

Now let’s take a look at what you might have discovered about your rules for commenting in three areas.

The human-inhuman sequence means that you ask yourself to live by a rule that is nearly impossible to keep: “No matter what happens, look happy.”

In the overt-covert sequence, some rules are out in the open, and some are hidden yet obeyed: “Don’t talk about it. Treat it as though it didn’t exist.”

Then there is the constructive-destructive sequence. An example of a constructive way of handling a situation is, “We’ve got a problem about a money shortage this month. Let’s talk about it.” An obstructing or destructive way of handling the same situation is, “Don’t talk to me about your money troubles——that’s your problem.”

Let’s summarize some of the things we’ve been discussing in this chapter. Any rule that prevents family members from commenting on what is and what has been is a likely source for developing a restricted, uncreative, and ignorant person, and a family situation to match.

If, on the other hand, you are able to get in touch with all parts of your family life, your family life could change dramatically for the better. The family whose rules allow for freedom to comment on everything, whether it be painful, joyous, or sinful, has the best chance of being a nurturing family. I believe that anything that is can be talked about and understood in human terms.

Almost everyone has skeletons in the closet. Don’t you have at least one? In nurturing families these are simply reminders of human frailty, and they can be easily talked about and learned from. Other families hide them away and treat them as gruesome reminders of the badness of human beings, which must never be talked about. It may be difficult at the outset to talk about these touchy matters, but it can be done. Talking helps everyone in the family learn how to risk such difficulty and survive——even improve——the situation.

Rules are a very real part of the family’s structure and functioning. If the rules can be changed, family interaction can be changed. Check into the kinds of rules by which you are living. Can you understand more now what is happen- ing to you in your family? Can you allow yourself to be challenged into making some changes? New awareness, new courage, and new hope on your part can enable you to put some new rules into operation.

The courage will come from letting yourself accept new ideas. You can discard the old and unfitting ideas, and you can select from those you’ve already found useful. This is just plain logic. Nothing remains eternally the same. Think of your pantry, the refrigerator, a tool shed. These always need rearranging, replacing, and discarding of their old contents and the adding of the new.

By now, you’ve thought about your rules and examined them. Why not check out your rule inventory against the following questions?

What are your rules?

What are they accomplishing for you now?

What changes do you now see you need to make?

Which of your current rules fit?

Which do you want to discard?

What new ones do you want to make?

What do you think about your rules? Are they overt, human, up to date? Or are they covert, inhuman, and out of date? If your rules are mostly of the second variety, I think you realize you and your family have some important and necessary work to do. If your rules are of the first category, you are probably all having a ball.