17. Family Engineering

Things don’t just happen by themselves, in a family or anywhere else. In this chapter, we are going to talk about family engineering. It isn’t too different from any other kind of engineering. In a family, like a business, getting the work done requires the management of time, space, equipment, energy, and people. To begin the engineering process, you find out what your resources are, match them with your needs, and then figure out the best way to get the results you want. Through this inventory, you will find out what you don’t have; then you will need to figure out a way to get what is missing. It is this process that I am calling family engineering.

One of the most frequent complaints I hear is that family members have too many things to do, too many demands, and too little time. Some of this burden may be relieved when your family works out more efficient ways to carry out your family engineering requirements. Take a good look at how you are doing things.

Periodically find out about the specific resources that each member has to contribute. As persons grow older and learn more, they keep adding to their resources. Keep the family up to date by doing this inventory often. Get in the habit of asking each other, “What are we now capable of?” If this question is asked in a leveling way, it will usually get a real answer. Most people like to help. They just don’t like to be bossed around.

Adults in particular forget that children can be of immense help. The more everyone participates, the more each feels an ownership in the family and the less any one person gets overburdened. If you are seven, you may be able to help Daddy in the garage. If you are five, you may be too little to do that, but you may be able to bring the silverware to the

table. On the other hand, maybe Johnnie, who is five, is more capable than Harry, who is seven. Some families limit help by such comments as ‘‘Women are not strong enough to . . . “Men don’t . . . .” Very few jobs around the family are gender linked.

So many abilities of family members——especially the children——are wasted. Children are not supposed “to be able to,” so their abilities are never really discovered. This not only makes the family tasks more burdensome, but deprives children of learning much-needed skills.

There would be far fewer harried fathers and mothers if children were not merely allowed but encouraged to use themselves more fully in the family and at an earlier age. One of the most rewarding experiences for any human being is to be productive. You’ll never find out how productive your kids are or can be unless you give them a chance to show what they can do.

How do you use four-year-old Paolo’s ability to move fast? Maybe you can use him as an errand boy when you are working in the tool shed. How do you use seven-year-old Anna’s ability at quick addition? Why not let her help you keep the household accounts straight? You can probably think of more ways in which your children can genuinely help you.

We all know that families live in different kinds of settings. Some live in big houses, some in little, some with lots of equipment, others with very little. Incomes can range from $100 a month to $50,000 a month, and the number of family members can vary from three to as high as seventeen or eighteen.

Given the same house, number of family members, income, and the same labor-saving devices, some people will feel their needs are met and some will not. Using one’s resources at a moment in time is also related to what one knows about those resources, how one feels about oneself and those one lives with. Put another way, the fate of the engineering department depends just as much on the self-esteem of the individuals, the family rules, the communication, and the family system as it does on the engineering plans and the things to be engineered.

Let’s look at the job situation first. Family jobs are frequently called chores. Although necessary, these jobs are often thought of as negative, a “somebody has to do it” kind of thing. It is still true that these chores form a major part of the family business and as such are important. The persons who do them can be given special attention.

I would like to propose something now that is similar to what you did in the Rules chapter. Sit down together and make a list of all the jobs that have to be done to make your family function. Agree on a secretary, as before. In your list you will include such things as laundry, ironing, cooking, shopping, cleaning, keeping accounts, paying bills, working at outside jobs, and so on. If you have pets or a garden or lawn, you will need to include these, too. If a family member needs special care, include that. These are the kinds of basic jobs that have to be undertaken regularly, not every day.

Now consult your list and see how these tasks are being carried out by your family. You will learn something as you do this. Perhaps you have never sat down and looked at your whole family picture in this way.

Are you finding out that not all the necessary tasks are getting done? Maybe you’ll discover that some things are done poorly or that too many tasks fall on one person and too few on others. If any of these things are true, someone in your family is being cheated and/ or feeling frustrated.

Done about every three months, this simple exercise helps to keep a perspective in the family’s engineering department. In business, this is where efficiency experts come in. Your list and what you do about it can become your guide to your own family efficiency.

Once you arrive at what needs to be done, choosing the best plan and the best person to get the job done is the next step and often the most difficult one. How do you decide who should or can do what and when? Most families find they have to use different methods at different times.

In what I call the edict method, a parent decides to use the authority of the leader and simply order what is to be done. “This is how it will be, and that is that!” I recommend that one use this method sparingly. When you do, take care to be congruent or you will have a rebellion on your hands.

Sometimes it is more fitting to use the voting method, the democratic way, in which the majority reaches the decision. “How many want to do it this way?”

Other times, what I call the adventure method works out the best. In this rather freewheeling approach, everyone states his or her views, and these are all tested against reality to see what’s really possible.

Still other times seem to require the expediency method. We all know this one. Whoever is available gets stuck.

All these methods fit some situations. What is important is to choose the method that best fits the particular situation at a particular point in time. Expect that everyone will keep her or his promise. This is excellent training for learning responsibility.

The word to watch out for is always. Too many families always use edict, always vote, and so on. And if always is lurking around your family engineering, somebody’s getting strangled. You will also find yourselves in the well-known, unenviable rut with open or covert rebellion in the wings.

Parents have to be able to say “yes” or “no” firmly. They also need the skill to ask, at times, “Well, what do you want to do?” Sometimes they’ll need the insight to recognize a situation in which they’ll say, “This is something you’ll have to figure out for yourself.”

I know some families, for instance, whose parents never decide anything——choices are always left “for the children.” Still other families have no leadership at all. Everyone sits for long hours in judgment on everything—— even as to whether Father should wear white shirts to the office. Other families are ruled solely by parental edict. Again, nothing about any of this is easy. We have to fall back on judgment——knowing when to do what.

Varying job assignments can do a lot toward minimizing the “chore” aspect of family functioning. Adults also need to accept the child’s work at his or her own level, and give up the expectation of perfection. Children who hear the comment, “It’s a sloppy job,” do not get a boost to their self-esteem.

Another trap is expecting that a plan, once made, will stay in force forever. An example of this is expecting a child to be in bed by 8:30 no matter what——or whether the child is four or fourteen. This is an out-of-date rule as far as the fourteen-year-old is concerned.

I know how tempting it is to look hard for the “one right way” and then use that forever. I believe that well- worked-out plans include a specific termination time——one

week, one month, one year, 3:30 today, when Mother gets back, or when you are three inches taller.

When a family is very young and the child is not yet old enough to walk, some adult has to pack the child around. As soon as the child can efficiently walk alone, parents should encourage it. The wise parent takes advantage of each evidence of growth in the child. The child can then do things alone and even help with other tasks. One concern is not to let the evidence of growth get lopsided. When a child first starts to walk, he or she may walk slower than the parent is willing to put up with. The adult might be tempted to pick the child up like a baby and stride off even though the kid could really do it alone.

Here’s another example. By the time children reach ten (and very possibly before) they could probably iron their own clothes. They certainly can help with the washing.

With the washing machines of today, a child of four could probably run the machine. The creative family makes use of all of these hands and arms and legs and brains, as soon as they are available, in the interests of both themselves and of the family.

Many children have told me that they think adults are in some kind of conspiracy to shove all the dirty jobs on kids and keep the pleasant jobs for themselves. Maybe there is something to this. If this is happening in your family, change it. It will be well worth it. No matter who is stuck with the drudge jobs, there can be creative, humorous, light ways to make fun out of the work. If not, you can at least feel a sense of accomplishment. Whoever has the dull jobs just shouldn’t be asked to look happy while doing them.

Again, I make a plea for flexibility and variation. The engineering in a family goes a long way toward providing each family member with some concrete evidence of value. Every person needs a feeling of mattering, of counting, as well as a feeling of contributing to what is going on. A child who sees herself or himself as someone who matters also gets the feeling that his or her contributions are honestly valued, are being considered, and are really being tried out by someone who needs help.

Now I think we need to talk about family time. We all have twenty-four sixty-minute hours available to us every day. But we work, go to school, and have many other activities that take this time from the family. How much family time does your family have? How much of it do you use for the family chores?

Some families use so much of their time for family business that they have no time left to enjoy one another. When this happens, family members often feel that the family is a place where they are burdened. The engineering begins to deteriorate.

Here’s a way to avoid this. Go over your job list and ask yourself two questions. Is this job really necessary? If it is, could it be done more efficiently or with more fun?

You may find that when you ruthlessly look at why you are doing this job, you’ll find that it was just “always done,” yet it really serves no purpose. If that is true, use your good sense and stop doing it.

This brings us to priorities. If the problem in your family is that family business squeezes out time for family members to enjoy one another, then I think you need to look carefully at your priorities.

I recommend that you start with the bare bones of what is necessary. Select those jobs that make the difference between life and death——the survival needs. Then, as time permits, other less pressing jobs can get done. Of course, this means you can feel free to change your priorities. To bring this into focus, I’m asking you to divide your family business into two categories: now and later. Obviously, the now category has the highest priority. How many family items of business do you have in this category? More than five items are too many. You may find that each day differs in terms of what is in which category.

The second category, “It would be nice and could be done later,” can be woven in as the situation permits.

Now let’s look at how you spend the rest of your family time. How much time is available in your family for contact with individual family members? Of the time spent in this contact, how much of it is pleasant and leads to enjoyment? When a large amount of contact becomes unpleasant, there is trouble. My experience is that in many families, by the time people get the work done, they actually spend very little time with each member of the family that yields any enjoyment, which makes it easier to see family members as burdensome and uncaring.

Every person needs time to be alone. One of the anguished cries I hear from family members is the need to have some time for oneself. Mothers in particular feel guilty if they wish to have time alone. They feel as if they are taking something away from the family.

Family time needs to be divided into three parts: time for each person to be alone (self time); time for each person to be with each other person (pair time); time when everyone is together (group time). It would be great if every family member could have each of these kinds of time every day. Making this possible requires first being aware that it is desirable and, second, finding ways to do it. With the external pressures we have, we can’t always manage all three.

Some extra special factors influence the use of family time in certain families. Some have to arrange their time in terms of the way they make their livings. Firefighters and police officers are examples. Some firefighters are on duty twenty-four hours, then of twenty-four hours. In police work, shifts change and can be irregular. People in other jobs may work on night shifts, as in bus and airline facilities that are open around the clock. People who work special hours have to invent new ways to participate in their share of family planning and family business.

Many families include a parent who travels for long periods of time. This arrangement can put great strain on the family unless members maintain a superb system of communication and make the greatest use of their time when the traveling parent is home. Otherwise this arrangement throws extraordinary weight on the parent left at home, decreasing his or her opportunity for self time and sometimes leading to chemical abuse, extramarital affairs, or overindulgence or overstrictness with the children.

Another special factor is the family’s size. The bigger the family, the more complicated the engineering. Time management can be pivotal. To help families take a look at this particular aspect of engineering, I have created a time/ presence inventory.

Have each person keep track of her or his whereabouts at certain times on two days, one a weekday, and one a weekend day. For each family member, divide a sheet of paper according to the hours in the day, starting when the first person gets out of bed and going on until the hour when the last person goes to bed.

If the first person gets up at 5:30 A.M. and the last one goes to bed at 12 A.M., your sheets would be divided as follows:

Have each member enter his or her location at these different times of the day. The next day, one person puts these all together, showing very dramatically what opportunities each family member had for self time, pair time, or group time.

I remember one woman saying after we had done her inventory, “My God, no wonder I feel lonely! I never see anyone but the cat!” (She had a very active family.) Indeed, families I’ve seen rarely have more than twenty minutes a day when all their members are together and can have group time. Twenty minutes to an hour a week is more like it. This means family business has to be transacted in twenty minutes, usually during mealtime. Everybody has to eat; transact past, present, or future business with one another; and take care of anything that comes up during that time, such as phone calls, people dropping in, or junior falling off the chair. That’s a big load to put on twenty minutes, and an even bigger load for people who want to grow in their knowledge, awareness, and enjoyment of one another.

If a family transacts family business without all members present, chances for misunderstanding are greatly multiplied. From time to time, of course, this does happen. When it does, problems can be minimized if someone is responsible for carefully noting what is going on so that she or he can give a clear report to the absent member, for example, “Last night when you were babysitting, Mother told us she is now going to work full time. We wanted you to know so you could start thinking about how this might affect you.”

Once we realize how important it is to keep all family members informed about all family business, we can make a practice of seeing who is absent and working out ways to give information to the absent member. Ways to do this include nominating a reporter or writing a note. This kind of thing goes a long way toward cutting down on the alienation of “I didn’t know” and “They do things behind my back.”

Passing on information is only a substitute for having someone there in person. But it does help. If trust among family members has slipped badly, it will be better to try to transact business only when all members are present, at least until new trust has been built up.

If the family habitually transacts business without all members present and also has little pair time, then some family members get to know each other primarily through a third person. I call this acquaintanceship by rumor. The problem is that most people forget that something’s a rumor and treat it as fact.

For instance, husbands often learn from their wives how their children are, and vice-versa. One child may tell a parent how another child is. In a family, regardless of whether one actually experiences the other members, everyone thinks he or she knows the others. How many children know their fathers through their own experiences with them? How many children get to know their fathers through their mother’s eyes? You can see what a dangerous practice this could be. It becomes something like that old parlor game, “Gossip,” in which someone whispers something in the ear of the person next to him, and it gets passed all around a circle of people. When the last person reports what she heard, it is nearly always totally different from what was originally said.

This communication-by-rumor often goes on in families. When families do not agree on group time to transact

family business, it is the best that can happen. In troubled families, this kind of communication is very frequent. There is no substitute for checking out your own perceptions and facts, hearing and seeing for yourself.

Communication affects how well the engineering is working. For instance, a wife announces to her husband that their son Tony, who is not present, did not cut the lawn today. The father may feel called on to discipline Tony. He may discipline without information or without considering why he is called on to do the discipline.

Having group time, of course, is no guarantee that family business will be transacted effectively. When you are together as a group, what happens? What do you talk about? Does most of the conversation concern faults of other persons, lectures by one or more members on how things should be? Does one person monopolize the time with long recitals of aches and pains? Is there silence? No talking? Are people perched on their chairs waiting for a chance to get out?

One of the best ways to find out about this is to make a tape recording of your family (videotape is even better, you have the equipment) and then play it back. If you don’t have a tape recorder, ask each member to take a turn observing what goes on and reporting back. Another way to do this is to ask a trusted friend to take over this duty. This can be an extremely revealing exercise, and will point out to you how easy it is for us to be unaware of how our family process is taking place.

Do you find that you use this time to get reacquainted with your family members, getting in touch with what life is like for each now and maybe what it was like this day? Is this a time when the individual joys and puzzles as well as the failures, pains, and hurts can come out and be listened to? Can you talk about new plans, present crises, and so on? Few families realize that every day they, as a group, go through a splitting-up and reconciliation process. They leave each other and come back together. While they are apart, life goes on for them. Getting together at the end of the day provides an opportunity for sharing what happened in the world “out there” and renewing their contact with each other.

A typical kind of day in many families could be something like this. The father gets up at, say, 6:30. He shaves and showers and then comes to the kitchen, where his wife had put out coffee the night before. He may grab some cereal. When he’s ready to leave the house, he awakens his wife. She gets up about 7:15 and makes breakfast for the six- year-old boy, who has to leave on the 8:00 bus. In the meantime, the fourteen-year-old girl got up early and is out doing some running practice. She will leave for school at 8:30 A.M.

Between 7:15, when Mother gets up, and 7:45, the middle child, a twelve-year-old boy, is in the bathroom get- ting ready. He pops into the kitchen just as little brother starts his breakfast. Having not quite finished his homework from the night before, the older boy sits at the other end of the table. They both take the same bus. They are quiet, thinking about what’s going to happen in school that day.

Mother is in the kitchen urging the children to eat. She’s watching the clock and is afraid that the children will be late. Finally, the older son gets off, giving mother a little peck on the cheek, and the younger son says, “Good-bye, Ma.” The daughter returns from running, prepares for school, and leaves on foot. Maybe a few minutes after this, Mother leaves for her job. Everyone has gone now.

In a few hours, the family members will start returning. The six-year-old will come back at 2:30 in the afternoon and go over to the neighbor’s. Mother comes home at 3:00 and calls the neighbor, who tells her her son is there. Then she gets busy with some laundry that she knew had to be done. After all, her husband needs some clean shirts, and the children need underwear.

The twelve-year-old boy is going to be at a Boy Scout meeting that day; the fourteen-year-old is going to have some kind of athletic practice.

At 6:00 when the husband comes home, the six-year- old is back from play, the twelve-year-old is out with the Boy Scouts, and the fourteen-year-old is expected home at 7:30. Wife, husband, and six-year-old all have a hurried dinner. Most of the conversation is about which bill should be paid first.

Then Father goes out to his poker game. The daughter comes home before Father returns and is asleep when he comes in. Father goes for a whole day without sharing any- thing of substance with his children. Although he is busy, he is interested in his children and might ask his wife how the children were. Of course, she doesn’t really know too much either——she’s seen them here and there. What she tells him might depend more on her feelings than her experiences or observations of the children. Many, many days can go on like this.

Such days form a continual parade of half contacts. It is easy to lose track of people and the relationships. The separation can be continual and prolonged. The result is that people feel isolated from one another. I have worked with families that found no reconciliation until they all came together in my office.

Families in this spot know that although they live together in one house, they do not have much real experience with one another. It is wise to get together once a day for everyone to touch base with each other. In the busy lives that most of us lead, this kind of meeting needs to be planned. It cannot be left to chance.

I believe the idea that families live together is more illusion than reality. This helps me understand much of the pain I encounter in families whose communication-by-rumor and half contacts pave the way for all kinds of distortions about how things really are in the family. Filling out a time/ presence inventory is a first step to making clear how much of your idea of your family is an illusion and how much is real. With a little planning, once you know what the problem is, you can make opportunities to really contact your family members. Maybe you can go on to make some changes, too.

Another aspect that plays a big part in how well the engineering works has to do with how each person experiences time. For instance, if you’re excited about something that’s coming up, time often seems to drag. When you are busy and involved with something you particularly like, time flies. The experience of clock time has no direct relationship to the experience of self time. Five minutes can seem like an hour, or it can seem like a minute. How different family members experience time is related to how things get done.

Experiencing time is an important part of predicting time. Predicting time is basic to carrying out commitments and directions. Many people get into difficulties with each other because one is often late. The immediate assumption, that the late one just wanted to bug the other, isn’t necessarily the case. It could represent a difference in the way each experiences time.

When little attention is paid to the individual’s experience and his management of time as part of the problem people often explain it as follows: “If you loved me, you would be on time.” This is a form of blackmail.

Children are often criticized for being late. And a lot of families try to deal with this tardiness by punishment rather than teaching.

When we come into the world, though, we know nothing about how to predict our time. This is something we learn slowly, over a long period. I think that learning about and using time is a very complicated kind of learning. Many adults still have difficulty with it.

Just think of all the factors we have to consider if we announce at 8:00 AM. that, “at 5:30 tonight I will be at such and such a place.” We then face a constant process of select- ing, rejecting, and managing all through the day with what- ever comes up so that we can be on time. How can we fill the time demands of the day? Can we gauge the transportation circumstances? What allowances can we make for interruptions? We set out to know enough about how this day can or will go, so that at 8:00 AM. we can assure ourselves and others that we’ll arrive at 5:30 P.M. It is really quite a miracle, if you think about it.

Think about yourself and your relation to time. Go back and look at your family’s time inventory. If the complexity of using time were more widely understood, people would show more understanding and less blame. Meanwhile, I would be willing to wager that in a great many families, children are asked to handle time in a way that the adults can’t do.

Many homemakers, female and male, get in trouble here. They agree to have the dinner ready at 5:30 P.M. As they go through the day, somebody calls up or comes to visit. Or the homemaker sees something that needs cleaning, or gets engrossed in a book. Suddenly it is 5:30, and he or she realizes supper is not ready. This creates situations that cause irritation. Others might call this person lazy or irresponsible.

The way each person experiences time is related to awareness, motivation, knowledge, and interests. It is an aspect of each person’s uniqueness. Getting acquainted with how each person uses time is an important factor in every relationship——no two people use it in exactly the same way.

If time schedules can be used as desirable guides rather than evidence of good character, we might come a little closer to eliminating some of the problems of scheduling. After traveling thousands of air miles, I find the airplane that is scheduled to depart at 3:47 sometimes doesn’t leave until 8:10. So I have developed a guide for myself, which goes like this: I will use the best judgment I have in making a time commitment. Then I will do the best I can to meet it. If it turns out that things don’t work out so I can keep my commitment, and I can’t change my circumstances, I don’t bug myself.

I was brought up on the sacredness of being on time. If I were late, I would be punished. N o matter what, I had to be on time. The result was, of course, that I was frequently late. With my current guide, things flow. I am rarely late. I don’t fight with myself anymore.

Without our knowing it, the clock runs many of our lives. Instead of being our aid, it becomes our master. Our

attitudes about time greatly influence our effectiveness in getting the job done.

For instance, many people follow a plan of rigid eating times. That means that at a certain clock time, everybody is expected to be at the table and the cook is expected to serve the food. Unfortunately, not everyone may be hungry. And the person who cooked may feel that people who don’t eat heartily at that moment don’t love the cook. I know this happens frequently. To avoid offending the cook, family members may grow fat or vomit after meals.

Not eating has nothing to do with loving the cook. It has to do with where that person is in terms of appetite. I am not necessarily making a plea for people to eat or not eat. What is important to me is that people do what fits for them. If they’re not very hungry, then they don’t have to eat very much. If they’re hungry, they can eat more. Clock time and self time do not always coincide. Happy people are flexible about this dilemma.

It’s rare that any two people are at exactly the same point at the same time. This goes for sex as well as food, and certainly for desires and wishes. When people are really aware that they can be in different states at different times, they make allowances. Instead of feeling put down, they can usually negotiate and come to some agreement. This may not always represent everyone’s druthers, but both people have a chance to have something.

I know a woman who sometimes wants to shop in the evening. She tells her husband of her wish, and he responds that he is a little tired but will go along if she doesn’t expect him to be too exciting. If she replies that that’s all right with her, the two of them sometimes also go to a movie.

Given that he can tell her about his fatigue, his feeling of having participated in the decision to go shopping may make his energy flow more, and he can end up enjoying a movie as well. He doesn’t have to fight the battle of who has the right to tell whom what to do, nor does he concede just to keep peace.

The idea that you have to be where I am is very expensive emotionally. In contrast, if this gal said to her husband, “I want to go shopping, and you’d better come,” he might go to avoid an argument but would probably not be a good companion. Then she could feel put upon, and the battle would be on.

If we waited for everyone to be exactly at the same point as everyone else, we might wait forever. If we require that other people be where we are, we run the danger of developing interpersonal difficulty. If we ask where people are and tell them where we are and then enter into some kind of negotiation, accepting each person’s current reality, something better can evolve.

The question then becomes: How can we let each other know our whereabouts, and how can we then find a place for each other so that we both benefit?

Every member of the family needs to count on some space and some place for privacy, free of invasion from any- body else. Whether it is little or big doesn’t matter, just so it is your own. It is easier for me to respect and value your place if I also have one that you likewise respect and value. Feeling that I have a place that’s assured tells me that I count. Not having this assurance often leads to the attitude, “I don’t care. So what? What difference does it make? I clean up the kitchen, and you mess it all up.”

How many times, for instance, have you heard bitter comment from one child about how another child has taken things or has invaded some personal space? Or have you heard a parent (perhaps yours) yelling because someone removed a tool from its “right” place? The same is true for anyone who is looking for something somebody else took and didn’t put back. just let yourself imagine how you feel when you worry about someone misplacing your belongings.

Being able to count on managing your own things and participating in decisions about how and when others will use your things is very important. This lets you feel that you count.

A clear, reliable experience in ownership paves the way for eventual sharing. It is a message of self-worth and therefore removes fears about sharing. I think a child needs to understand clearly, “This is mine and I can do what I want with it.” Some parents buy one child a toy, for instance, with the expectation that the toy will be shared with an- other child. Then they get upset because the sharing doesn’t work. If the toy is to be a house toy, a shared toy, then it should be so designated from the start. Very often conflicts erupt because neither child feels assured in matters of privacy and ownership.

Sharing, to me, is the decision by one person to let another person in——to belongings, to time, to thoughts, or to space. It is another one of those complicated learnings that take a long time to grasp fully. People can share only if they feel trust. Parents often ask children to share before they know how to, and then punish them for bad results. In these same families, I rarely see evidence that the adults have learned to share successfully.

At this point, you may have done the necessary work that enables you to have a clear, firm list of the jobs it takes to make your family run. You may also have some new awareness about your priorities. No engineering would be necessary if no people existed. Engineering is necessary only because it can make the lives of people better. If it makes the lives worse, then you need new engineering.

Through what I have asked you to focus on in this chapter, you may now have more ideas about how you can be less burdened and more hopeful. What ties the whole engineering aspect together is an efficient, well-understood information system, which operates in a context of trust and humanness.

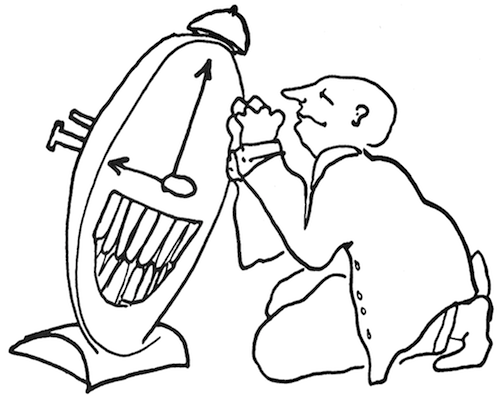

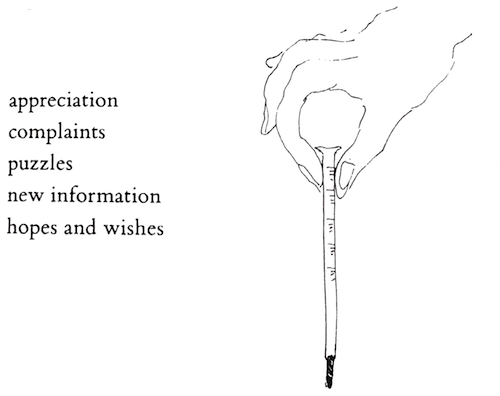

To make all of the above easier, I recommend a family temperature reading. I developed this process to keep the emotional climate clear in a family (or any group of people who work or live together) so that the group’s necessary business can be transacted and the lines of communication among the members can be kept open. The aim is to put words to areas of life that are present with all of us yet are not often talked about directly. For lack of a better word, I will call these areas themes.

The first theme is appreciation. We feel good when we share our feelings of appreciation toward others and ourselves. To give a voice to these feelings is to keep a balanced internal state. To share appreciations with others is to give them an unsolicited gift. How often do we take these feelings for granted and not express them? This theme enables us to make conscious, verbalized, appreciation messages.

The second theme deals with the negatives of life: complaints, worries, and so on. We all have these too. I invite the person who has a complaint to accompany that complaint with a recommendation for change. The next step will be to ask for the help to make that change. This is quite a different approach than expecting someone else to deal with your complaint or defend themselves against you.

The third theme concerns puzzles, which are the gaps that come about naturally when many people are together. Who can think of telling everyone everything that is going on? To do that, we would need a very sophisticated message system. Even businesses goof in this way. To meet this, give yourself permission to say what your puzzles are. Puzzles often occur when people forget, misspeak, or don’t hear. It is hardly ever because people are perverse. The important part is to keep things straight. This is a way to do it.

Because of the interactions between family members and the outside world, or between other family members, individual persons often have new information, which is a fourth theme. This is often related to puzzles. It is easier to remember what you have in the way of new information if you have a structure to remind you of it.

The last theme is the theme of hopes and wishes for ourselves, which are dear to all of us. Many times, we shortchange ourselves because we choose not to put words to our hopes and wishes for fear they might not happen. We will never know what can happen until we do articulate our desires. The other important part is that when you put words out. your loving family members may be able to help you. You may be able to do the same for them when they put out their dreams. We do little alone.

Five themes occur on the thermometer for our family temperature:

Make a large “thermometer” with these five readings. Paint it; or make it out of cloth or felt. Make it colorful. Have fun with it. Hang it in a room where your family is likely to sit together and do temperature readings.

Invite all family members to sit comfortably, preferably in a circle. Have a tape recorder handy in case you want to record and listen back later. Agree ahead of time how long you want to take——a half hour, fifteen minutes, or an hour. Have someone be a timekeeper. Ask someone else to write down those things that might not get finished and have to be dealt with later.

While you are learning, it is helpful to take the temperature themes in order. For example, each person who wants to can speak about appreciations. Then ask for the complaints and continue with all the other themes.

It is important to remember that this is all voluntary. Not everyone will have something to say about each theme each time you have a temperature reading. The spirit is to listen and, when responding, to clarify and add rather than correcting or influencing. Apply this to tough things as well.

The most important aim is to give a voice to all the themes by everyone who wants to talk. Be flexible. Do not hurry! A hug by all members at the beginning will show good will. A hug at the end will be a thank-you.

At the beginning, it will be helpful to plan temperature readings at least once weekly. After you have some experience and doing this seems familiar, comfortable, and helpful, try to have ten-minute temperature readings every day.

I said this would keep the emotional climate clear. Regular temperature readings raise everyone’s trust and self-esteem. We also continue learning about each other and becoming closer and freer. You will find as a result that your engineering tasks become more creative as well.